Note: Before beginning this portfolio, decide when you'd like to take your class to the library for research instruction. It's best to schedule a session at the start of Portfolio 2, before students begin researching their issues more extensively. Call Cathy Cranston to set up an appointment (she'd prefer that you call two weeks ahead of time).

This portfolio marks a shift from focusing on the arguments advanced by individual authors - that is, focusing on individual positions on an issue - to understanding the larger conversation about that issue. Four related concepts, each connected to the conversation metaphor that runs through the course, will help you and your students make the shift from focusing on the ideas articulated by individual authors to focusing on the shared concepts that underlie most publicly debated issues:

Accountability: Inexperienced writers might think that developing an argument about a public issue is as simple as stating a claim and supporting it with evidence. Doing so, however, results in an argument that fails to account for what’s already been written about the issue. Writers need to be accountable members of a conversation - that is, they should take time to listen to the conversation. They should read what other writers have contributed to the conversation; they should learn what types of evidence are valued by people involved in the conversation; they should figure out what’s the current topic of the conversation is. Failing to become an accountable member of the conversation not only increases the likelihood that an argument will fail, it demonstrates a lack of respect for the ideas and information that other members of the conversation have brought to the conversation.

Newness: The flip side of the obligation to be accountable is the obligation to contribute something new - something of value - to the conversation. Simply rehashing the arguments and rehearsing information that others have contributed to the conversation does not meet this obligation. Newness, fortunately, comes in several flavors. You can offer something radically new - the kind of newness that might win a Nobel prize, such as John Nash’s suggestion that not all situations involve winners and losers, and that in fact there are “win-win” situations. If you see your students providing this kind of contribution to an issue, please let the other members of the composition faculty know about it. A second kind of newness is a new way of looking at an issue, perhaps by suggesting new a new analogy or by providing a new analytic framework for understanding the issue, much as cognitive psychologist Herbert Simon did when he suggested that we can understand certain economic decision-making processes by examining them through the lens of cognitive psychology. A third kind of newness involves providing new facts or details that enhance our understanding of an issue, such as new first-hand accounts from victims of a particular natural disaster, a new interpretation of an event or work of art, or results from a scientific study that replicates earlier work. In fact, the third kind of newness is the most common kind of newness found in writing - or in life, for that matter.

Positions: When an author makes an argument, he or she is taking a position on an issue. A position is a specific claim made by an individual author. In the first Portfolio, your students defined the positions of individual authors in their summaries. They staked out their own positions on an issue when they wrote their responses.

Approaches: When a group of authors have positions that are fairly similar, you can say that they take the same approach to the issue. An approach is an interpretive device that helps you figure out how to make sense of a complex issue. Rather than trying to remember 30 or 40 positions on an issue - and make fine distinctions among them - you can define three or four approaches to the issue. Examples of approaches include the pro-life and pro-choice approaches to the abortion issue. Literally thousands of people write about this issue in a given month, and close analysis will indicate that there are subtle differences among each position. It’s easier for us to think about the issue in terms of pro-life and pro-choice approaches, however, even though doing so tends to obscure those subtle differences between approaches.

In this portfolio, your students will be making the shift from focusing on individual positions to understanding the similarities among positions that allow them to create approaches to an issue. This portfolio begins with identifying an issue that interests them, determining what their potential readers might know about that issue, creating an annotated working bibliography, grouping their sources into approaches, and conducting an analysis of those approaches.

The key in this first week of the portfolio is helping students understand what a debatable issue is and how they can explore it. By encouraging your students to select a debatable issue that interests them, you’ll increase the likelihood that they will produce better writing, since students are more likely to write well about issues they care about. We want students to be invested in their issues so that they will think critically about them and so that they revise their writing more willingly. We also want students to apply concepts involving the writing situation (context, audience and purpose) to their own thinking about writing. This goal is achieved by having them write for a public audience of college students. Even in the initial stages of their research, students will need to think about which topics are most relevant to their audience. The library instruction will help students hone their research skills and teach them to seek out current, credible, and valid sources.

![]() WTL - Postscript for essay one (10 minutes):

Use this activity to encourage

students to reflect on their writing for Portfolio 1. Have them address

questions such as: What part of this writing process was most valuable to you

and why? Which parts of this essay were most challenging? How did you overcome

these challenges? What did you learn about writing or about yourself as a

writer while completing Portfolio 1?

WTL - Postscript for essay one (10 minutes):

Use this activity to encourage

students to reflect on their writing for Portfolio 1. Have them address

questions such as: What part of this writing process was most valuable to you

and why? Which parts of this essay were most challenging? How did you overcome

these challenges? What did you learn about writing or about yourself as a

writer while completing Portfolio 1?

Note to instructors: Postscripts are useful when evaluating student writing because in them students tend to recognize their own struggles. This frees you from labeling such struggles as "problems" within your comments. Rather than directly stating that a student needs to develop a claim, state that you agree with the student's own observation that development is something that needs more consideration. This approach creates a tone of, "I'm here to help you" as opposed to, "I'm the expert."

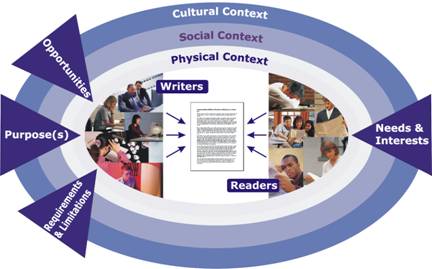

![]() Transition between Portfolio I and Portfolio

2 (10 minutes): Revisit the writing situation model from

Portfolio I to explain the transition between Portfolio I and Portfolio 2. This

will help students see where the course is heading.

Transition between Portfolio I and Portfolio

2 (10 minutes): Revisit the writing situation model from

Portfolio I to explain the transition between Portfolio I and Portfolio 2. This

will help students see where the course is heading.

You can draw the model on the board or on an overhead and use it to explain that:

· We begin as readers who encounter texts as a way to learn and explore what is happing culturally and socially.

· Then, we become informed readers - drawn to certain specific issue that we want to learn more about.

· We read and research various texts to locate the "conversation" that surrounds the issue we're interested in (find out what groups or individuals, who are active in writing about the issue, are saying).

· Then, we analyze these texts to figure out how they are shaped by cultural and social influences. In turn, we consider how the texts that get produced are shaping society and culture.

· Once we've critically examined the existing viewpoints on an issue, we become critical thinkers and informed writers. We then use our observations and critical thinking skills to construct new arguments.

· We write our own arguments for public discourse (that is, for a specific group of readers in society who are arguing about an issue publicly) in the hope that our opinions and views will influence that argument.

· Through this process, we become active participants in society and culture.

Cultural Contexts

· Language / Media

· Government

· Shared cultural values and beliefs

· Common traditions

· Larger historical events (e.g. "Roe V. Wade")

Social Contexts

· Organizations, universities, schools, churches, businesses, environmental groups…

· Family, friends and neighbors

· Shared values and beliefs among smaller groups

· Local events and traditions

· Community concerns (e.g. planning for growth along the front range)

Explain the shift from readers to writers:

In Portfolio I - you begin as readers exploring issues and forming opinions

In Portfolio 2 - you choose your own issue; then you research this issue and analyze the various approaches to writing about it

In Portfolio 3 - you become participants, writing arguments based on the research and critical thinking you've done in Units I & II

![]() Introduce Portfolio 2 (15 minutes): Distribute all four assignment sheets and let

students read through them. Fill in due dates, highlight key points, and

address students' concerns along the way. Try to help them understand the sequencing

for these assignments; and emphasize that all parts lead up to the Issue

Analysis which is intended for an audience of college aged readers. (For more

assistance with planning this activity, read the section on "Planning to

Introduce an Assignment" in the teaching guide, Planning a Class, on

Writing@CSU (https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/planning/).

You can also find a copy of the Guide in your appendix.

Introduce Portfolio 2 (15 minutes): Distribute all four assignment sheets and let

students read through them. Fill in due dates, highlight key points, and

address students' concerns along the way. Try to help them understand the sequencing

for these assignments; and emphasize that all parts lead up to the Issue

Analysis which is intended for an audience of college aged readers. (For more

assistance with planning this activity, read the section on "Planning to

Introduce an Assignment" in the teaching guide, Planning a Class, on

Writing@CSU (https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/planning/).

You can also find a copy of the Guide in your appendix.

![]() Discuss Topics and Issues (10 minutes): The first step in writing for Portfolio 2 is

to have students choose issues to work with. Emphasize that students will be

sticking with the issue they choose for the remainder of the course (9 weeks)

so they'll want to pick something they're interested in. The goal for this

activity is to help students think about choosing topics and narrowing their

topics into specific issues. Inform students that topics are too broad for

the issue analysis and that they'll need to narrow their topics in order to

focus their writing for Portfolio 2. Use the grid below (or one that you

develop) to illustrate the differences between topics and issues. Also, point

out that issues are often defined in the form of a debatable question.

Discuss Topics and Issues (10 minutes): The first step in writing for Portfolio 2 is

to have students choose issues to work with. Emphasize that students will be

sticking with the issue they choose for the remainder of the course (9 weeks)

so they'll want to pick something they're interested in. The goal for this

activity is to help students think about choosing topics and narrowing their

topics into specific issues. Inform students that topics are too broad for

the issue analysis and that they'll need to narrow their topics in order to

focus their writing for Portfolio 2. Use the grid below (or one that you

develop) to illustrate the differences between topics and issues. Also, point

out that issues are often defined in the form of a debatable question.

|

Topic |

Issue |

Issue |

Issue |

|

Nuclear Waste |

Where should we store it? |

How should we transport it across the country? |

Should we continue to use nuclear energy when we don't have a reliable solution for storing its waste? |

|

School Violence |

What is the cause of the recent school violence? |

What should teachers' role be in managing school violence? |

Should the government fund more counseling programs in schools to reduce violence? |

![]() Brainstorm possible topics and issues (10 -

15 minutes): Have students generate a list of topics on

the board (ones that would interest them and other college students). Then,

practice narrowing these topics down to specific issues. If you want to assign

this as a homework activity, consider using the brainstorming, freewriting, or

looping activities in the CO150 Room in the Writing Studio on Writing@CSU.

Brainstorm possible topics and issues (10 -

15 minutes): Have students generate a list of topics on

the board (ones that would interest them and other college students). Then,

practice narrowing these topics down to specific issues. If you want to assign

this as a homework activity, consider using the brainstorming, freewriting, or

looping activities in the CO150 Room in the Writing Studio on Writing@CSU.

![]() Develop criteria for what makes a "good

issue" (10 - 15 minutes): Since writing situations (purpose, audience, and context) determine

what makes an issue "good" - begin this activity by asking students

to consider their audience and purpose for writing their issue analysis. You

may review the various audiences and purposes (as listed below). But emphasize

that while students may have various audiences and purposes in mind, their

primary audience for their issue analysis should be college students. Their

primary purpose should be to show that their issue is complex.

Develop criteria for what makes a "good

issue" (10 - 15 minutes): Since writing situations (purpose, audience, and context) determine

what makes an issue "good" - begin this activity by asking students

to consider their audience and purpose for writing their issue analysis. You

may review the various audiences and purposes (as listed below). But emphasize

that while students may have various audiences and purposes in mind, their

primary audience for their issue analysis should be college students. Their

primary purpose should be to show that their issue is complex.

|

Audience |

Purpose |

|

College Students |

To show that an issue is complex |

|

You (the writer) |

To analyze your issue as preparation for writing an argument in Portfolio 3. |

|

The Instructor |

To prove that you can think critically about the writing situation (connections between readers, writers and culture) by analyzing an issue for college aged readers. |

Here are some criteria to include for what makes an issue "good":

· Your issue should appeal to college students (including yourself).

· It should be complex enough to move beyond a simple pro/con debate.

· It should be popular enough to find a range of opinions on (informative sources such as news reports are useful for learning about the issue, but convincing or persuasive sources, those that take a position, are needed for the analysis portion of the writing).

· It should be fairly current or it should represent an ongoing concern.

· It should build off of existing arguments. For example, you wouldn't want to research an issue that has already been explored over and over (e.g. "Does the media negatively affect a woman's self image?") This question lends itself to no surprise since it has already been asked many times. Rather than "reinventing the wheel" find out how an ongoing conversation has evolved. See what direction it has most recently taken. Then, build on that recent thread of conversation (e.g. "Much research has already shown that fashion magazines have a negative effect on a woman's self image, but little work has been done to see how magazines affect men. With the production of men's magazines on the rise, perhaps we should begin to consider these effects.")

![]() WTL - Practice narrowing topics down to

issues (10 - 15 minutes): Have

students list two or three topics that they might be interested in researching.

Then, have them narrow these topics into 3 - 4 specific related issues. Since

you've already modeled this activity as a class, you probably won't need to

thoroughly explain it. Verbal instructions or instructions on an overhead

should be sufficient.

WTL - Practice narrowing topics down to

issues (10 - 15 minutes): Have

students list two or three topics that they might be interested in researching.

Then, have them narrow these topics into 3 - 4 specific related issues. Since

you've already modeled this activity as a class, you probably won't need to

thoroughly explain it. Verbal instructions or instructions on an overhead

should be sufficient.

![]() Peer Review (10 - 15 minutes): Have students exchange their WTL's in either

pairs or groups. Ask them to read each others topics and issues and then decide

which ones would best meet the criteria for what makes a "good"

issue.

Peer Review (10 - 15 minutes): Have students exchange their WTL's in either

pairs or groups. Ask them to read each others topics and issues and then decide

which ones would best meet the criteria for what makes a "good"

issue.

![]() Discuss context and audience for the Issue

Analysis (10 minutes): Be sure that you and your students have

visited the Talking Back website before conducting this activity. Keep

in mind that your students will be thinking a lot about their readers, college

students, in Part II this portfolio, so focus more on context and the details

of the actual website for now.

Discuss context and audience for the Issue

Analysis (10 minutes): Be sure that you and your students have

visited the Talking Back website before conducting this activity. Keep

in mind that your students will be thinking a lot about their readers, college

students, in Part II this portfolio, so focus more on context and the details

of the actual website for now.

Here are some points that you should touch on:

· Let students know if you plan to publish any of their essays on Talking Back. Usually instructors will allow several students to submit their papers (post essays on SyllaBase), but will only publish the one that the class votes on.

· Ask them to describe Talking Back and discuss the site's Mission Statement. Then, ask them to describe what type of essay might get published here (given the founders' purpose and intentions for the site).

· Explain that issue one is comprised of media analysis essays but issue two will be made up of issue analysis essays (thus, students should not use the posted essays as models since they're working with a different assignment). However, you may discuss ways that former CO150 students appealed to their college aged readers and whether or not it was effective (tone, language, style, content, evidence…)

· Explain that students and instructors can enter Talking Back through the CSU writing center, but the published essays are also available though search engines. Given this larger context, ask students what they'll need to think about. (Their research will need to be accurate and credible, and their writing should be focused and cohesive. Their essay should also read like it was written for a public audience, not as a response to a school assignment) .

![]() Introduce Topic Proposal (5 minutes): Review the assignment sheet with students and answer any questions they

may have. Remind them to do some preliminary searching (talk with people about

their issue and read two or three sources)before completing this assignment.

Tell them that they do not need a bibliography page, but they should use author

tags to credit ideas in their proposal.

Introduce Topic Proposal (5 minutes): Review the assignment sheet with students and answer any questions they

may have. Remind them to do some preliminary searching (talk with people about

their issue and read two or three sources)before completing this assignment.

Tell them that they do not need a bibliography page, but they should use author

tags to credit ideas in their proposal.

![]() Review Tannen's essay, "The Argument

Culture" from the PHG (15 minutes): Facilitate a discussion for Tannen's essay. The goals for this

discussion should be: to help students understand what is meant by the

"dialogue" or "conversation" surrounding an issues, as

opposed to a debate; to discuss the importance of looking at all sides when

seeking "truth" on an issue in culture; and to explain the connection

between Tannen's essay and the Issue Analysis Essay for Portfolio 3. For more

assistance with planning this activity review the teaching guides on Planning

a Class and Leading Class Discussions on Writing@CSU and in your

appendix.

Review Tannen's essay, "The Argument

Culture" from the PHG (15 minutes): Facilitate a discussion for Tannen's essay. The goals for this

discussion should be: to help students understand what is meant by the

"dialogue" or "conversation" surrounding an issues, as

opposed to a debate; to discuss the importance of looking at all sides when

seeking "truth" on an issue in culture; and to explain the connection

between Tannen's essay and the Issue Analysis Essay for Portfolio 3. For more

assistance with planning this activity review the teaching guides on Planning

a Class and Leading Class Discussions on Writing@CSU and in your

appendix.