Day 2 (Thursday, August 28)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals. Identifying thesis statements and writing collaborative summaries give students practice with summary writing; developing questions for further inquiry will engage students in ongoing inquiry that will be useful in Phase 1 and Phase 2 assignments.

Prep

Before today's class, be sure you have reread "Responses to the IPCC" and “Why Bother?,” created an "inquiry list" of questions and terms from Tuesday's WTLs, and written your own lesson plan.

Materials

Inquiry List

Prentice Hall Guide (“Responses to the IPCC” annotated for each author's thesis and reasons)

Printout of “Why Bother,” annotated for thesis and reasons

Overhead Transparencies:

Identifying Thesis Statements activity instructions

Group Summary Activity instructions

Homework (or make handouts for homework—do the same thing that you did on Tuesday)

6 blank overhead transparencies (you can get these from the mailroom in Eddy)

6 overhead markers, such as Vis a Vis (you'll need to supply these yourself)

Lead-In

For today's class, students have read "Responses to the IPCC” and “Why Bother,” have looked for thesis statements, have either attended the climate change lecture or watched a similar one via podcast, and are expecting to discuss the readings and the lecture. It's not uncommon to have a few students come to class the second day without having done the homework, or for new students to show up. Any unprepared student can join with a peer to look on with the reading and will be able to follow along during class. Arrange a way to help students with any problems (couldn’t log on to Writing Studio, bought the wrong textbook, etc.), but plan on a quiz or other means of holding students accountable for the reading assignments. Remind students of the upcoming limited add/drop policy deadlines. Refer them to the yellow sheet you handed out on the first day.

Activities

If you arrive to class a few minutes early, you might write the "agenda" on the board. A brief list of today's activities could go something like: "Quiz / Discuss lecture and readings / Identify thesis statements / Introduce summary / Further inquiry." If you choose to do this, make it a reliable routine.

Tip. Daily quizzes or WTLs that you collect are easy ways to make sure your students take reading assignments seriously, and can act as useful catalysts for discussion.

Introduction. Begin today's class by previewing the planned activities: Today we are going to continue talking about climate change and we'll discuss how to write an academic summary.

Attendance (2-3 minutes)

Take care of any remaining registration issues (such as new students or students that were absent on the first day), and be sure to note which students are absent. You might take attendance by asking each student to report the most interesting or confusing aspect of the climate change lecture.

Tip. Taking attendance by asking students a question is a good way to get them involved in the day’s activities, though it can easily eat time if you’re not careful.

Reading comprehension quiz (5 minutes)

It’s important to consistently hold students accountable for class reading assignments, and a fairly easy five-question quiz is a good method of doing so. Another option is to have students complete a WTL which you collect and evaluate. Whatever you choose, introducing your preferred method on Day 2 is a good way to signal that students need to keep up with their reading. Here’s a sample quiz you might put up on an overhead:

1. What is the IPCC’s “AR4”?

2. With which holiday did its release coincide?

3. How does Robert J. Samuelson of the Washington Post suggest we respond to cries to “do something”?

4. Why does Michael Pollan recommend we all plant gardens?

5. What’s the difference between “climate” and “weather”?

Transition. Before we discuss the quiz, let’s talk about academic inquiry for a few minutes.

Discuss academic inquiry (3-5 minutes)

Explain the inquiry list. Here’s a sample explanation:

As we work over the next few weeks, we will be keeping track of the questions and terms we want to know more about. I started a list as I read your WTLs from Tuesday. During each class session, someone will be in charge of adding questions raised by our reading and discussions to the list.

Read a few things from the list, and then assign a “list-keeper” for today. The "list-keeper" should listen especially carefully during discussions to make a record of the ideas and questions that come up. The list-keeper can also add questions of his/her own.

Transition. Let’s begin our discussion today by going over the answers to the quiz.

Discuss "Responses to the IPCC" and “Why Bother” (10 minutes)

Ask students how they answered the quiz questions and then move to broader questions to evoke discussion, such as "Which writer did you agree with most?" or "Which of these arguments seemed written most persuasively?" As students offer answers, encourage them to talk to each other by rephrasing their comments as you understood them and asking another student if he or she agrees, or asking "Who had a different reaction?" Don't hesitate to ask for clarification. If your students are very reluctant to speak, give them a WTL and then ask for some responses. If your students are overly-exuberant, keep track of time so that you can move forward with class after 10 minutes or so.

Tip. Calling on students by name will make them feel more engaged with the class, keep momentum up in the discussion, and give you more opportunity to memorize their names.

Transition. These reactions show that, often, writing gets a conversation going.

Introduce the idea of writing as conversation (3-5 minutes)

Explain the ways in which writing is similar to conversation. Here’s a sample explanation:

Like a conversation, writing involves exchanges of ideas that help us shape our own ideas and opinions. It would be foolish to open your mouth the moment you join a group of people engaged in conversation—instead, you listen for a few moments to understand what’s being discussed. Then, when you find that you have something to offer, you wait until an appropriate moment to contribute. We all know what happens to people who make off-topic, insensitive, inappropriate, or otherwise ill-considered remarks in a conversation.

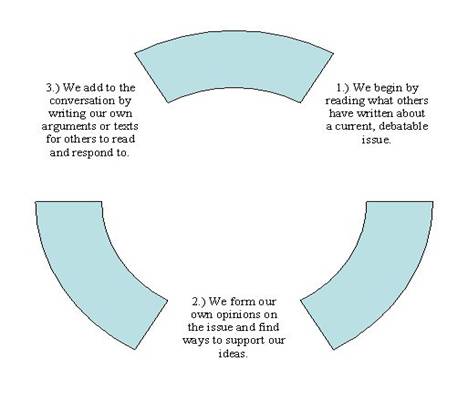

The following is a visual representation of the way in which this course is designed around the writing as conversation metaphor. Before explaining, present it to students on an overhead, or draw it on the board:

Tip. This image can be enlarged to make a more visible overhead.

Once the students can see the image, explain:

Right now, we are at the first stage: reading what others have written. That is, we are listening in on the conversation. Later in the semester, we will conduct research to form our own opinions and add to the conversation.

Next, explain why you asked students to look for thesis statements. Here’s a sample explanation:

An important part of academic inquiry is being able to set aside ones’ own biases and preconceived ideas and really listen to what others are saying about the question-at-issue. This isn’t to say that readers don’t have reactions and responses but that it’s essential to be able to distinguish between subjective reactions to what the writer has said and an objective understanding of what the writer has said.

Transition. We rarely begin a conversation with a thesis statement announcing what we will say; likewise, writers don’t always begin with a thesis statement.

Group activity: identifying thesis statements (8-10 minutes)

Take time to define "thesis statement." There are many ways of defining this term; for our purposes a definition such as "the main idea that the writer wants to communicate to readers" works well. You might ask students what other words they’ve associated with “thesis,” such as “central claim,” “primary argument,” etc.

Tip. You might point out that a thesis is often a response to a critical question, and ask students to think of questions the “Responses to the IPCC” writers are trying to answer.

Now, give students a chance to practice this in small groups. Give instructions for group work on an overhead before you divide students into groups, and then assign them one of the IPCC responses from the PHG.

Identifying Thesis Statements

Work with your group to identify the thesis statement in one of the "Responses to the IPCC" essays.

If you disagree, try to figure out why, and try to reach a consensus.

In a few minutes, you'll report your findings back to the class.

Have students count off from 1 through 4 to create groups (all 1’s will group together, all 2’s together, and so on). Direct groups to specific areas of the room to work. Give groups a chance to say "hello" to each other, and then remind them of the task at hand.

It probably won't take groups a lot of time to do this; float among the groups to get a sense of their questions and keep them on task. Ask the first two groups finished to come to the front of the room and write the thesis statement they came up with on the board.

Once you have two theses on the board, talk them through with the class. Ask groups to explain why and how they identified this particular thesis, and ask the class if they agree with this group's identification. You can refer to your own notes to add on to (or to correct, if needed) what the groups have come up with. Remind students that thesis statements don't always come in the first paragraph, nor are they always neatly packaged in one obvious sentence.

Transition. Being able to find the writer's thesis statement is essential to writing an academic summary, which is the first writing assignment we'll do in this class.

Introduce summary writing (10-15 minutes)

Tip. Summaries demonstrate that students comprehend what they’ve read. The summaries that students write will enable us to assess their ability to distinguish between subjective reactions and objective understanding of a text’s argument.

Tip. This is a key moment of learning for students. They're probably used to being told how to write a particular kind of document.

Introduce academic summary by explaining that summaries require one to set aside one’s own biases and preconceived ideas and really listen. On the board, write:

Academic Summary

Purpose: To offer a condensed and objective account of the main ideas and features of a text; to demonstrate your accurate comprehension of a text.

Audience: Your instructor

Make sure students understand what "objective" means, and then ask students to talk about how they might go about writing a summary that accomplishes the above purposes for the audience. That is, how can students write a summary that will show you, the instructor, that they have understood what they have read?

Give them time to think through your question, and be encouraging about even minor suggestions (provided they apply—if a student says "write about why I disagree," for example, don't validate that because it will confuse everyone in the class). Below "Purpose" and "Audience" on the board, make a list of "Strategies." Once students have offered everything they seem to have, take time to assess the list of strategies. If there's anything that seems off, clarify it. If anything essential is missing, add it and explain why you are adding it. It's ok if this list isn't 100% complete because students will read more about writing summaries for homework, and you will cover it more in class next week. In a perfect world, the following would be on the list in some form (explanations you might give are in parentheses):

Use Pollan’s “Why Bother” and model the process of summary writing for students. Start with the thesis, and then help students identify key points. Here's an example:

Start by writing "Michael Pollan, ‘Why Bother,’ The New York Times, and April 20, 2008" on the board.

Ask students what they took to be Pollan’s thesis. (Something like "Since climate change is caused by our daily choices, we must change our lifestyles, and a powerful way of changing is to plant a garden.") Write this on the board, and then introduce the concept of "key points."

Tip. A way to determine whether or not a statement is a reason or if it is evidence is to see if it can be grouped with similar statements in the essay. Locate yourself or ask your students to find other examples of statements dealing with the ethics of climate change mitigation or the urgency of the problem.

Often, key points are reasons or "because" statements that support the thesis. Sometimes they are not phrased with the "because" conjunction, though they could be. Ask students to find specific language in Pollan’s essay that explains why he thinks we should, indeed, “bother” to change our lifestyles. Possibilities include: "A sense of personal virtue," “laws and money cannot do enough…it will also take profound changes in the way we live," "The Big Problem is nothing more or less than the sum of countless little everyday choices, most of them made by us," "you will set an example for other people," “Consciousness will be raised, perhaps even changed,” “You quickly learn that you need not be dependent on specialists to provide for yourself,” etc.

How do these statements differ from ones like "For Berry, the ‘why bother’ question came down to a moral imperative" and “we have only 10 years left to start cutting—not just slowing—the amount of carbon we’re emitting”? The difference, mainly, is in scope—the statements quoted in the paragraph above are broader and use general language; they are reasons. The statements quoted in this paragraph are narrower and give specifics; they are evidence that support the reasons. Writers often offer several pieces of similar evidence to prove a reason; Pollan has done so in this essay.

With a thesis and some reasons listed, you’ve got a good start. But does this cover all of Pollan’s main points? Not really; arguments often contain more main points than just a thesis and reasons (sometimes they offer concessions, refute counter arguments, or suggest solutions; these things do not offer direct reasoning for the thesis, but still they are integral parts of the argument). In Pollan’s case, he has included an alternative to his thesis: he says that “There are so many stories we can tell ourselves to justify doing nothing, but perhaps the most insidious is that, whatever we do manage to do, it will be too little too late.” This is another key point, though it is not a reason for the thesis (saying "We should change our lifestyles because we think it won’t make any difference" doesn't make logical sense). Leaving this point out of the summary altogether, though, would be misrepresenting the text.

On the board, now, you should have the basic things that would need to go into a summary of Michael Pollan’s essay. Ask students how they would turn this list into paragraphs. How long might the summary be? Might you incorporate quotes?

Transition. Since I'm asking you to write a summary for homework, I'd like to give you a chance to practice writing one here in class.

Group summaries (20-25 minutes)

In this activity, students will work in their small groups to complete the same tasks you just worked through on the board, and to write the summary in paragraph form. They should continue on with the same essay they used in the previous activity. Explain the group work instructions (on an overhead transparency) and then give groups time to work.

Tip. Circulate around the room to answer questions and to keep track of how much time the groups will need. You need a few minutes after this activity to assign homework.

Group Summaries

Work with your group to write a summary of one of the essays in "Responses to the IPCC":

First, read the essay closely and make an outline like the one we just did together

Then, come up to the front of the room to get a blank transparency and an overhead pen.

Write an academic summary in paragraph form. Please write your summary on the overhead transparency so that we can look at it next week during class.

Once all (or most) groups are finished, collect the transparencies and markers. Talk about the writing process, and ask if students have questions about writing summaries.

If you run out of time. Begin Tuesday's class by finishing the activity, which is better than rushing students—if groups are still working hard with five minutes, explain that we'll finish the activity next time and collect pens and transparencies (in case any students are absent).

If you have extra time. Choose one summary to put up on the overhead and discuss with the class. You don't need to evaluate it on the spot; you can ask students "How accurate is this summary?" or "Is it objective?"

Transition. For homework you have a new article to read and summarize—this one by Edward O. Wilson.

Assign Homework for Tuesday (3-5 minutes)

Conclude class

Conclude class by saying something like, next week we will continue with our work of academic inquiry by working more on summary and by generating inquiry questions as we talk further about issues related to climate change.

Connection to Next Class

On Tuesday, you will continue on with concepts you introduced today. Identifying a writer's argument will get more complex as we ask students to read more complex articles, so you'll need to spend more time with that. Students will be self-evaluating their summaries on Tuesday as well; to model that, you can use one of the groups’ summaries from today's class.