Day 7 (Wednesday, September 5)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

Today’s class provides a formal introduction to the concept of rhetorical situation and its terminology, and begins to show students how to talk about how a text works rhetorically.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Understanding rhetorical situations applies to every writing assignment students do in this class as well as in other contexts.

Prep

Today’s class may require a lot of prep. You’re introducing complicated concepts. To be confident in teaching the material for today, you might need to spend considerable time reviewing the rhetorical situation model and the related terminology. Developing several ways to explain context to students will help you meet their needs, as that tends to be the most difficult concept for CO150 students to grasp.

Materials

Inquiry list

Overhead transparencies:

Postscript questions

Conversation model

Rhetorical situation graphic

Rhetorical situation questions

Your textbook

Instructions for group work (unless you choose to conduct a class discussion instead)

Lead-in

For today, students have revised a summary and are preparing to turn in the first graded assignment of the semester. You will also make the transition from close to critical reading.

Activities

By now you probably have a routine established for beginning class. Write out your own introduction for today--remember to preview the day’s activities and to keep the inquiry list going. Since it’s been 5 days since you’ve seen your students, it’s a good idea to remind the class of what you did last time.

Chat with your students for a few minutes, asking them to talk about how they revised, what they did with the workshop feedback, etc. It can be great for your classroom culture if your students will talk about specific useful feedback. Asking a question like, “what was the most useful idea you received in workshop?” can get a discussion going that can reinforce the value of workshop. If your students don’t want to get specific, ask them to talk generally about the experience of writing and revising summaries.

Alternative: have students write their postscripts first, then discuss their responses.

Next, put “postscript” questions on the overhead and give students a few minutes to answer them. You might ask them to write answers on the backs of the summaries they’re about to turn in. We do a postscript at the end of each graded assignment, and this allows students to reflect on the writing process as well as to communicate with you about their writing. The postscript shouldn’t be an opportunity for students to vent or otherwise complain, so you should construct your questions carefully. Think about what kinds of things you want to hear as you grade your students’ writing. Questions like “what did you get out of workshop?” or “what should we do differently as we work on our next assignment?” leave students very open to give all kinds of feedback that’s not directly relevant to their writing process and/or the final product they are about to turn in, and can be saved for a mid-semester evaluation. You may want to review the postscript questions in each chapter of the Prentice-Hall Guide for more ideas about writing postscript questions.

General postscript questions follow that tend to work well for most any assignment. Feel free to modify them to suit your students’ needs and to suit each assignment. When you put the questions on an overhead, be sure to add instructions that tell students where to write their answers, where to put the postscript (if they’re turning in a portfolio), etc.

Postscript Questions

1. Are you satisfied with your final draft? Why/why not?

2. With what did you find yourself to be most successful as you worked on this project?

3. With what did you struggle most? How did you overcome that struggle?

4. What did you do to revise? How did you use your workshop feedback?

5. Is there anything else you would like me to know about your writing process as I read your final draft?

Collect summaries from students and explain your grading practices (i.e. you use the same criteria for every summary, you read closely and carefully, you write comments for them that are intended to help them learn about writing and about ways to improve for the next assignment, it’ll probably take about a week for you to grade the summaries, etc. Depending on your and your students’ dispositions, you might also remind students that a lot of CO150 students don’t earn high grades on the first assignment).

Transition our next project will build on the close reading techniques we’ve been learning.

To transition students into critical reading, spend a few minutes reviewing what it means to read closely. Students have this knowledge now, so you can rely on them to explain it to each other. Get them started with a question like, “what does it mean to read closely?” and record their answers on the board. Leave some room to one side so that, in a few moments, you can compare critical reading with close reading.

Remind students of the writing as conversation metaphor. If they seemed to pick up on this well last week, you can ask “in what ways is writing similar to conversation?” or you can explain it again. Have the conversation model overhead handy so you can remind them that the class is designed with this metaphor in mind. Right now we’re still in stage 1 (reading what others have written), but we’re no longer reading only to understand the writer’s argument.

Transition we’re going to continue reading about our question-at-issue (what should we eat?), but now we’re going to be evaluating what we read as well.

Ask for student ideas regarding the concept of critical reading. If students get caught up in “criticism” and “criticizing,” present them with the alternative phrase “active” reading. What does it mean to read actively? What can you do to/with a text beyond reading closely?

List student ideas on the board next to your “close reading” list. There will be some overlap, since it’s impossible to read critically if you’re not also reading closely. Let students come to this realization on their own; if they don’t, be sure to point it out. Here is the language that the PHG uses to describe critical reading: “Critical reading simply means questioning what you read. You may end up liking or praising certain features of a text, but you begin by asking questions, by resisting the text, and by demanding that the text be clear, logical, reliable, thoughtful, and honest.” Students will read more about critical reading for homework, so it is not essential that you cover all of the ground now.

Observe the lists you’ve made on the board, and ask students to point out similarities and differences. The major difference is that close reading involves finding out what a writer is saying, and critical reading involves evaluating how (and how well) a writer has composed his/her text.

During this discussion, you may also want to talk about the role of critical reading in academic inquiry to help students understand why we do it. For example, understanding how an author addresses purpose, audience and context can help us evaluate the quality of information and arguments.

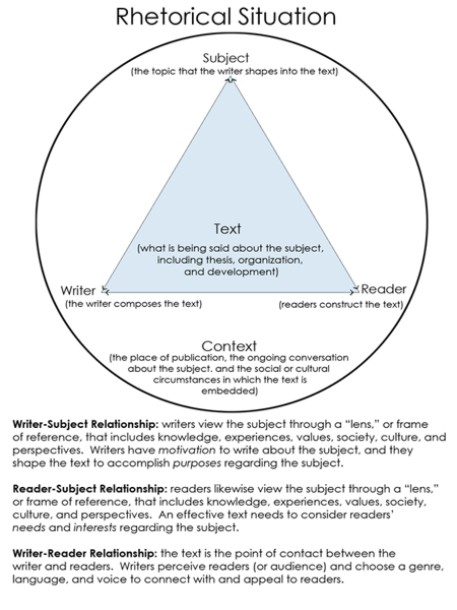

To begin looking at how the text is composed, readers need to ask questions about the rhetorical situation. Your students likely have never heard of “rhetorical situation” (though they may have heard the same concept referred to as the “writing situation”), so this will be new to students. Introduce the key terms and relationships with the Rhetorical Situation graphic on the overhead [link to high res Rhetorical Situation pdf graphic in appendix]

Next, show students questions they can ask to find out about the rhetorical situation (see pages 161-162 of the PHG).

Questions for Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

Writer and Purpose

Who is the writer? What does the writer know about the subject?

What is the writer’s frame of reference (or lens or point of view)?

What is the writer’s purpose?

Reader/Audience

Who are the intended readers?

What do these readers likely know and think about the subject?

What assumptions does the writer make about the readers’ knowledge or beliefs?

Occasion/Genre/Context

What is the occasion for this text?

What genre is this text?

What is the cultural or historical context for this text?

What key questions or problem does the writer address?

Thesis and Main Ideas

What is the writer’s thesis?

What key points support the thesis?

Organization and Evidence

Where does the writer preview the text’s organization?

How does the writer signal new sections of the text?

What kinds of evidence does the writer use (personal experience, descriptions, statistics,

interviews, authorities, analytical reasoning, observation, etc.)?

Language and Style

What is the writer’s tone (casual, humorous, ironic, angry, preachy, academic, other)?

Are sentences and vocabulary easy, average, or difficult?

What key words or images recur throughout the text?

Once a reader has answered these questions, he/she can go on to respond and evaluate, asking questions like: “is the overall purpose clear?” and “does the writer misjudge the readers?” and “did the tone support or distract from the writer’s purpose or meaning?”

The above questions show that close reading is embedded within critical reading—it’s important to know what a writer says and how he/she says it before we go on to offer our opinions about how well the text works.

Transition there are many new terms here; we're going to take some time to work through them as we discuss the upcoming readings. Critical reading is crucial to effective inquiry, so we will spend plenty of time on it in the next several classes.

Remind students what it means to inquire, and generate a list of ways in which Michael Pollan inquires. How does he decide what to inquire into? How does he find answers to his questions? Where does he position himself as he inquires? What does he do with his inquiries once they’re complete? Will he ever be able to “complete” his inquiry about food? etc.

Next, point out that we are inquiring as we’re reading and discussing these articles. Generate a list of ways in which we have been inquiring. Add to this list any ideas students can think of for ways in which we could push our inquiry further.

In the first two weeks of lesson plans, we included “if time” activities as well as some suggestions for ways to manage if you run out of time. No teacher can predict with 100% accuracy how long his/her class will need for certain activities, and so it’s important to think through some lesson plan alternatives before class. By now you probably know if your class tends to get carried away with some kinds of activities and/or if they finish some activities very quickly. It’s a good idea to have one relevant activity on hand that serves not just to fill time, but, more importantly, to enhance existing activities and concepts. Also, it’s a good idea to think through (and write down) what you can cut out or modify if you run short on time.

Assign the following for homework, collect the inquiry list and then wrap up class by reviewing key concepts from today and explaining what students can expect next time.

Homework for Friday

Read about rhetorical situations on pages 17-29 of the PHG, and read about critical reading on pages 157-163.

Access, print and read “An Animal's Place”[remind students how to access the reading]. Try out one of the critical reading strategies explained on pages 160-163 (either a double-entry log or a critical rereading guide). You may hand write or type this. On Friday, bring your double-entry log or critical rereading guide, your textbook and “An Animal’s Place.”

Find the Writing a Letter assignment sheet in Assignments on the Writing Studio and print it out to bring to class. [add this item to the homework if you choose to handle distributing assignment sheets this way]

Connection to Next Class

Next time you’ll come back to the rhetorical terminology you introduced today, and you’ll discuss one of Pollan’s longer pieces. Students will be able to see common strategies Pollan uses as he writes, and they may begin to compare "An Animal's Place" to the shorter Pollan articles they've read.