To introduce the course, yourself, your policies, the course texts, and your students to one another. Begin to address writing as a situated activity (a series of choices made for a specific audience and purpose within a given context). Introduce the concept of "Writing as Joining a Conversation."

The interview activity establishes communication necessary for peer reviews and classroom discussions. The review of course concepts establishes familiarity with ideas that will be returned to and developed throughout the course.

Make sure everyone is in the right course and section by putting your name, the course number, title, and section number on the board. This helps students who have wandered into the wrong room and let's them know immediately who you are. Expect a few students to arrive late on the first day-many are getting used to a new campus.

When you introduce yourself, clarify what you would like your students to call you. Recall our discussion of professionalism/formality from training: how formal you are regarding your name plays a role in the tone you set for your classroom from this day on. Be prepared, though, for students to make mistakes and call you the incorrect name or default to calling you "Professor" or "Mr./Mrs." out of habit or lack of comfortableness.

Hand out the yellow Add/Drop sheet given to you in your mailbox. Emphasize that students cannot drop the course after the date on the yellow add/drop sheet you handed out--no if's, and's or but's. They also cannot withdraw from CO150 as they might from other courses. If they want out, they must do it by the drop date, which is generally the end of the first week of classes.

Call out names and record attendance on your roll sheet. Also write on the roll sheet any nicknames as well as phonetic pronunciations of difficult names. While you'll probably use some other attendance-taking measure in the future (such as collecting homework), taking the time to call roll during the first few days will help you learn students' names. Once you've gotten through your roll, ask if there is anyone you missed.

Use transition statements to connect activities for your students. Most teachers write down a few notes on their lesson plans to remind themselves of what they want to say between activities and then weave the transitions into the natural flow of conversation during the class session. This helps students see why activities are relevant and how they fit into the lesson. We are not asking you to read the suggested transitions here like a script. Use the transitions in this syllabus to the extent that works best for you and ultimately construct your own transitions before class or in an impromptu fashion.

Sample Transition: CO150 is a discussion based course. We'll take advantage of the relatively small class size to work together in collaborative activities and to offer each other feedback on our writing. So, before we get started today, let's take a few minutes to get to know each other.

Have students pair up with someone sitting nearby. They should find out the other person's name, major, interests, and 1 distinct or interesting thing about themselves. Then, ask students to introduce one another to the class. You might have them state the person's name and 1 interesting or memorable thing about them.

If you have time, you could add a challenge to this activity. Once students have been introduced, see if each person can remember one thing about another student. You should start the process (i.e. "That's Amanda and her grandfather was a pro baseball player"). Then, Amanda has to remember something about someone else (i.e. "That's Jonathan and he has fourteen siblings"). Then, Jonathan picks another student and so on until everyone has gone. If the game gets stuck, ask students who haven't gone to raise their hands or to offer hints. Also, in order for the last person to have a chance to "play" you should restate your name and something interesting about yourself before the game begins.

Sample Transition: Explain that before you present the class with your expectations for the course, you'd like to find out what the students expect. You might say: Before I present you with my expectations for the course, I'd like to see what you expect from it.

A "Write-to-Learn" (WTL) is a pedagogical tool often used in CO150. Tell students they can expect to do WTLs frequently to help them collect their thoughts, jump-start a discussion, reflect on a text they read, or generate ideas for papers. Let students know whether you will always collect their WTLs or if you will collect them at some later point (at the end of each week or with their portfolios, for instance). (See the "Collecting Homework" section in the introduction to the syllabus.)

Have students take out a piece of paper and write for five minutes about their expectations for CO150. What do they think the course will be about? What do they hope to learn? What do they think will be most challenging? You can put these or other questions on the board or on an overhead. When students are finished, collect the WTLs and tell them you'll read their responses and address them during the next class.

Sample Transition: The course policy statement will help you understand the expectations for this course. Hopefully, it will address some of the concerns you just brought up.

Present the course policy statement, emphasizing the policies that you consider most important. Be sure to explain at least the following:

You may want to have a copy of your policy statement on an overhead with essential ideas highlighted. If not on the overhead, just having your own highlighted copy can help quell those first-day jitters and prevent you from forgetting anything critical. Or, delegate some of the responsibility by having students read sections aloud.

Other things to highlight:

Sample Transition: Now that you have seen a general overview of what this class entails, let's review some concepts that are central to this course.

First, introduce the terms: purpose, audience and context. Explain to students that experienced writers often think actively about their purpose, audience and context and that this is something we hope they will get into the habit of doing.

Cover these points in any order that feels right for you. You may choose to write this information on the board or present it on an overhead.

Purpose - Writers have purposes. Maybe their purpose is to simply inform. Or perhaps they want to convince readers to agree with their ideas. Or, they may just want to entertain. There are many purposes for writing.

At this point, you might ask students to think about their own purposes for writing. You could ask them questions like:

Audience - Writers think about their audience so they can successfully achieve their purpose. First, they need to determine who their audience is and what they are like. Then they might ask: What does this audience know about my subject? How will they feel about my ideas? What can I do to make them view me as credible and trustworthy?

Ask students to think about how audience might play a role in meeting their own purposes. For example, you could say:

Context - In addition to audience, writers need to think about their context. Here, context refers to the situation or circumstance that surrounds a piece of writing. Context includes things like:

Have students consider how context influences their writing:

Once students are comfortable with purpose, audience and context, tell them there is one more basic concept you'd like to cover today: Writing as Conversation. You may explain this concept in whatever way makes the most sense to you.

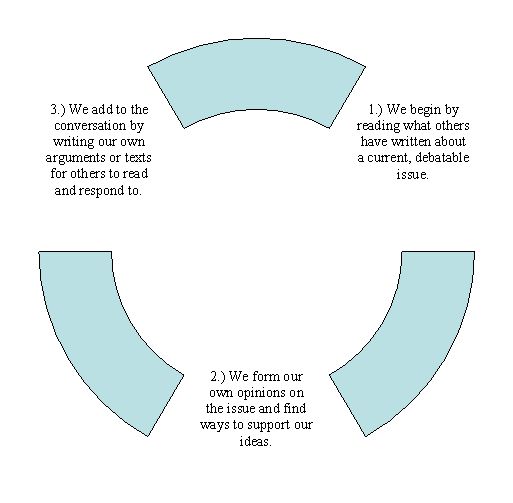

Here's our explanation: Writers who think about purpose, audience and context are usually involved in what we refer to as a conversation. They write as a way to participate in an ongoing dialogue on an issue. Unlike the writing we often do for school (which can sometimes feel forced or detached) this kind of writing is very purpose driven. We call it a conversation because, like a conversation, the exchange of ideas continues to build until writers arrive at some answer or truth.

In order to participate in a conversation, writers need to know what has already been "said" and where the conversation is currently headed. They don't want to risk seeming naïve or uninformed by repeating what others have already pointed out (i.e. "Save the rainforest." Or, "The media has a liberal bias!") Rather than reinventing the wheel, writers would do better to research what's already been said about an issue and then build off it by adding something new to the conversation (i.e. "The media's perceived liberal bias may affect the way people currently view the war in Iraq").

CO150 relies heavily on reading and research so students may become informed and accountable for what's been said before joining the conversation.

You may want to present the ideas above visually by using the graphic below. You could put it on an overhead or draw it on the board.

You might say something like: The first "conversation" that we'll take part concerns the topic of racial and cultural issues in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. For next class, you'll read two different articles concerning this issue.