Week 6: Activity Ideas |

The suggested activities for this week include: This week begins your weekly outline of goals/activities for Portfolio 2. Notice that the activity times will NOT add up to a complete week of class time; you will need to add your own activities to fulfill the weekly goals in your class sessions. As always, remember to introduce and conclude your lessons with previews and reviews. Use transitions to maintain a connection between daily classroom activities, assignments, and portfolio and course goals. |

Transitioning Between Portfolios |

It is important to transition clearly between portfolios for students. This way, they get a clear sense of where they've come from and where they're going - and they can see why. Think of a major transition like this one the same way you think of transitioning between activities in a class period: you want to provide an intellectual turn indicator for your students. Introduce Portfolio 2 (5-10 minutes)Distribute all assignment sheets—Topic Proposal, Annotated Bibliography, Issue Analysis and Synthesis—and let students read through them. Fill in due dates, highlight key points, and address student concerns along the way. Try to help them understand the sequencing of these assignments, and emphasize that all parts lead up to the Issue Analysis and Synthesis, which is intended for an educated audience of college readers—the class and their instructor. You may need to make a special case for the helpfulness of completing the Position Analyses for Single Sources and the Composite Grid homework assignments, since these are process elements of the Annotated Bibliography. For more assistance with planning this activity, read the section on "Planning to Introduce an Assignment" in the teaching guide, Planning a Class, on Writing@CSU (https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/teaching/planning/). Introduce the Topic Proposal (3-5 minutes)Review the assignment sheet with students and answer any questions they may have. Remind them that their goal in this portfolio is to research a topic that an academic and public audience needs to know more about. However, the primary audience for Portfolio 2 is themselves and the rest of the class. Tell them that they do not need a bibliography page, but they should use author tags to credit ideas in their proposal. Write a transition that explains the shift students must make from readers to writers as they move through the portfolios (3-5 minutes)For example:

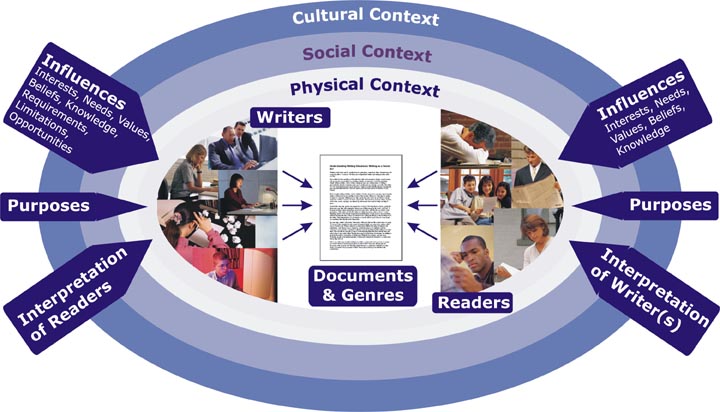

Transition between Portfolio 1 and Portfolio 2 (10 minutes)Revisit the Writing Situation Model from Portfolio 1 to explain the transition between Portfolio 1 and Portfolio 2. You can draw the model on the board or on an overhead and use it to explain that:

Write a transition that moves the classroom discussion from topics/issues to the contexts that form and explain participant views on those topics and issuesPoint out that students will be reading the Times with this new focus in mind during Portfolio 2. Specifically, students should continue to clip articles but now with the idea in mind of capturing both dominant and conflicting values, beliefs, and attitudes in U.S. culture. For instance, articles on educational issues suggest that there is a dominant belief in the essential right and obligation of all U.S. citizens to obtain at least a high school diploma—a "right" long protected by law and taxation. At the same time, "reform" movements are currently challenging the efficacy of public education and the current trend seems to be toward the privatization of education. |

Discussion Questions: Tannen's Article |

Reviewing Tannen's essay "The Argument Culture" is important since Portfolio 2 aims to avoid us contributing to the "argument culture" by becoming knowledgeable members of all the sides in the conversation so that we can create a dialogue instead of a cacophony of monologue-diatribes about publicly debated issues. The goals for this discussion should be: to help students understand what is meant by the "dialogue" or "conversation" surrounding an issues, as opposed to a debate; to discuss the importance of looking at all sides when seeking "truth" on an issue in culture; and to explain the connection between Tannen's essay and the Issue Analysis Essay for Portfolio 3. Facilitate a discussion for Tannen's essay (10 minutes)Questions you might ask regarding Tannen's essay include:

Note: For more assistance with planning this activity review the teaching guides on Planning a Class and Leading Class Discussions on Writing@CSU.

Review the day’s activities (3 minutes)When you or a student does this, take special care to make clear their connection to both Portfolio 2 and larger course goals. Take care to provide some sort of conclusion to each class. |