Week 10: Monday, October 27th - Friday, October 31st

Week 10: Monday, October 27 - Friday, October 31

Note: The beginning

of Portfolio 3 marks a new stage in your lesson planning. You are now

responsible for creating nearly all of your own activities to accomplish the

course goals. To support your efforts to accomplish this task, we have provided

detailed discussion of teaching goals. Also, you may consult the “Activity

Bank,” which is offered as a supplemental source in the materials for this

course and also will be available (and continuously enlarged upon) in the

Teacher Resources of the Online Writing

Center. We encourage you to

integrate the course texts, the PHG and the New York Times, as

well as technology components--the Online

Writing Center,

Writing Studio and Syllabase--into your lesson planning If you have any

questions about developing your lesson plans, please see Mike, Steve, Kate,

Sarah, Kerri, Paul, Liz or Sue.

Please remember to provide

lesson and course connections each class day and to introduce and conclude your

lessons along with providing helpful transitions between activities.

Goals for this week:

- Create a

transition between the second and third portfolios.Consider

asking students to complete a WTL/postscript for Portfolio 2 before you

collect the portfolios.

- Get

students reading nearly all of Chapter 10 of the PHG. Start

with pages 441-455.

- Engage

students in reading and collecting the Editorial and Op-Ed pages

from the New York Times as well as examples of graphics, photos,

and other visual forms of story and argument development as demonstrated

in the Times. Here you are continuing the News Clip Journal,

with an emphasis on (1) argumentation and (2) the use of visuals or

graphics for story/argument development.

- Review the

Writing Situation Model (see Resources, below) and introduce the “Great Circle of

Writing” model (see Resources, below).

- Introduce Portfolio

3 and the Context Comparison.

- Review

techniques for Writing Arguments (consider assigning pages 442

- 443 in the PHG and the

Argument writing guide on Writing@CSU.

- Brainstorm

arguments, claims, readers and contexts for Portfolio 3 (see

Resources, below).

- Review

types of claims on pages 444 - 448 in the PHG. To

accomplish this, introduce different types of claims from the reading by

designing a discussion that highlights the need to have a claim that is

debatable and to understand the expectations that come with different

types of claims they might use. Have students identify the types of claims

addressed in the PHG reading

(fact, cause-effect, value, solution) and how each type implies certain

expectations for supporting it.

- Discuss

what claims imply about development, reasoning, and evidence. Ask

students to consider the types of evidence they’ll need based on the types

of claims they might have. For example, a claim of value would necessitate

a list of criteria, while a claim of solution would likely require

evidence to prove both that a problem exists and that this solution would

work or is better than other possibilities. Also, remind students that

types of claims will suggest different types of proof. The PHG is set up to focus on different

types of claims in different chapters. Ask students to review the chapter

that deals with their type of claim.

·

Type of Claim:

Value: See "Evaluating"

Chapter

Solution/policy: See

"Problem-solving" Chapter

Cause-effect: See "Cause-effect"

Chapter

Fact: See "Informing"

Chapter

- Practice

unpacking claims. To accomplish this goal, consider preparing

sample claims that you can unpack as a class to prepare students for the

group activity. For instance, a claim of solution - such as Grades

do not accurately represent a student's intelligence; therefore portfolios

should be used instead - may work well because typically it

will imply a claim of value as well. To unpack this claim, a writer would

need to address all implied claims, including:

- the

criteria for intelligence (value)

- grades

fail at representing these criteria (fact)

- portfolios

will do a better job of meeting the criteria (fact)

Your discussion of a claim will

depend on the audience and existing research. For example, if research has already

shown that grades don't reflect intelligence, a writer could quickly

support this sub claim and then focus on the solution -- using portfolios

instead. However, if there is no evidence to support the claim that grades fail

to represent intelligence, the focus for the argument should be on proving this

claim.

- Workshop

claims in class. A typical workshop might involve asking

students to determine what type of claim is being made (fact,

cause-effect, value, solution), then “unpacking” the claim to determine

how many sub-claims are involved in it, identifying the types of evidence

needed to support the sub-claims, considering how readers might react to

the claim and sub-claims, and offering suggestions for revising and

narrowing the claim.

- Provide

students with an example of a single Context and Audience Analysis

(see appendix) and review it in class. Suggest the differences

involved when analyzing two differing contexts.

- Work on the Context Comparison in class (due

at the beginning of Week 11 - Mon., November 3 or Tuesday, November 4).

Connection to Course Goals

After creating a transition between Portfolios 2 and 3 and

connecting these to course goals, the two main objectives for this week are to

have students construct their claims and arguments and to have students think

critically about how their target audience and context will influence the

choices they make when writing their arguments. Use the PHG to introduce students to classical forms of argumentation, but

also emphasize that audience and context are as important as "forms"

when making choices about content and organization. To write successfully,

students will need to think about their readers' needs and interests and shape

their arguments accordingly. The Context Comparison is designed to help

students analyze writing for two different, real-world audiences. It serves the

overall goals of encouraging students to be active participants in culture and

enabling them to write for audiences beyond academia.

Required Reading and Assignments

- Read

the beginning of the Arguing chapter in the PHG, pages 441-455

- Read

the Arguing writing guide on Writing@CSU

- Draft

a claim for your argument and post it to the SyllaBase Class Discussion

Forum

- Read

and respond to the claim posted above and below your own. Is it clear

narrow and debatable? What advice can you give to improve the writer's

claim?

- Read

a sample (from the appendix) of a Context and Audience Analysis applied to

a single publication. As a class or in groups, have students discuss the

effectiveness of the sample and ask them to explain how it would need to

be altered for the demands of the comparison they’re being asked to do.

The goal is to set a standard for the Context Comparison (since too many

students will skim over the questions without enough thought if you don't

set a high expectation). Emphasize that students will need to do

substantial research in order to succeed on this assignment. Their efforts

here will contribute to their success with the final argumentative essay.

- Do

investigation into publications for the Context Comparison (due Week 11).

- Read

and clip editorials and op-ed pieces as well as graphics and visuals from

the Times with a goal of including 10 Editorials/Op-Ed pieces and

10 examples of visual storytelling or argumentation. Begin analyzing the

editorial/op-ed pieces for argumentative elements and structures. Also, as

you search the Times for examples of visual argumentation and story

development, ask yourself: How does this visual enhance or alter my

understanding of the story? What message do I take from it? How does my

interpretation differ from others’ interpretations? Connect visuals to the

current assignment, asking yourself whether tables, graphs, photos, etc.

would be useful and appropriate argumentative tools for the publication

you have in mind.

Resources

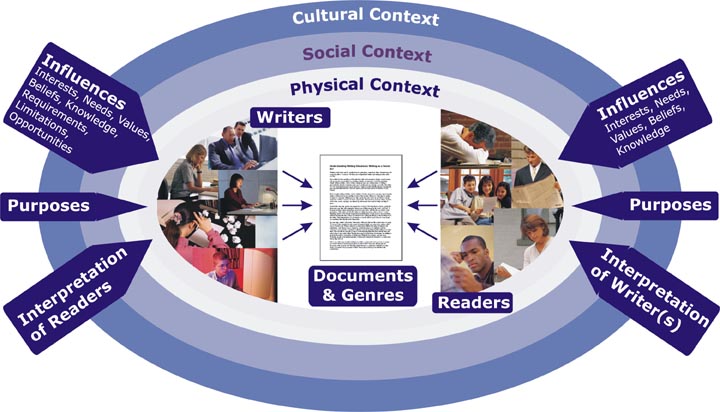

Review The Writing Situation Model:

Key points from the Writing Situation Model: Be sure to

cover the following points (in whatever order feels right for you):

·

Writers have purposes for writing

·

These purposes usually emerge from the writer's

cultural or social context (something happens outside the writer that creates a

need to write - something to respond to)

·

Writes make choices based on the context they

are writing for (writing a letter home to your parents asking for money is a

different than writing a letter to an organization to ask for contributions for

a good cause). Therefore, different contexts will pose different requirements,

limitations, and opportunities for a writer.

·

In addition to context, writers also need to

think about readers.

·

Readers have various needs and interests, which

are likewise determined by their contexts (their background, environment and

experience).

·

In order to communicate effectively, a writer

must anticipate what their readers' needs and interests are.

·

Cultural and social contexts shape the writing

situation, acting on both writers and readers. Key elements of cultural context

include language/media, government, shared values and beliefs, historical

events. Key elements of social context include organizations, universities,

schools, churches, businesses, environmental groups; family, friends, and

neighbors; local events and traditions; community concerns (such as planning

for growth along the Front Range).

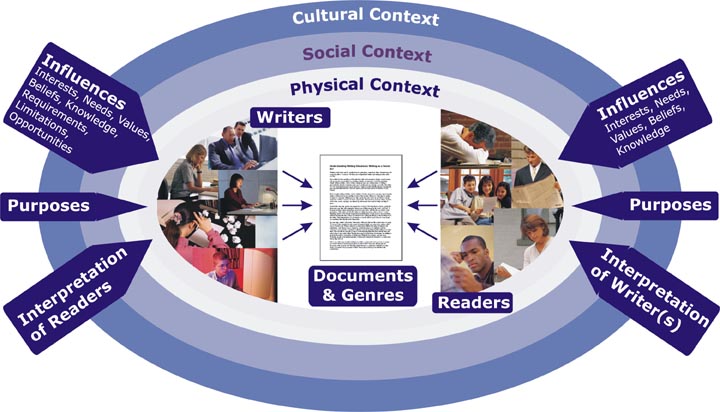

Introduce The

“Great Circle of Writing” Model: This model helps students see the shift

in their roles as writers that takes place as they join, learn about, and now

contribute to a conversation about a publicly debated issue.

Points to bring

up about the Great Circle of Writing Model:

- We

begin as readers who encounter texts as a way to learn

- and

explore what is happing culturally and socially. (Portfolio 1)

- Then,

we become informed readers - drawn to certain specific

- issues

that we want to learn more about. That is, we became accountable members

of the conversation. (Portfolio 2)

- We

read and research various texts to locate the "conversation"

that surrounds the issue we're interested in (find out what groups or

individuals, who are active in writing about the issue, are saying).

(Portfolio 2)

- Then,

we analyze these texts to figure out how they are shaped by cultural and

social influences. And in turn, we consider how the texts that get

produced are shaping society and culture. (Portfolio 2)

- Once

we've critically examined the existing viewpoints on an issue, we become

critical thinkers and informed writers. We then use our observations and

critical thinking skills to construct new arguments. (Portfolio 3)

- We

write our own arguments for public discourse (a specific group of readers

in society) in the hope that our opinions and views will influence society

and culture. (Portfolio 3)

- Through this process, we become active

participants in society and culture. (Portfolio 3)

Sample Brainstorming Activity for Developing Claims and

Arguments: The goal of this activity is to help students formulate

possible arguments and claims for their issue. This activity takes place in

front of the class using the white board. Lead students through one of the

following strategies.

Strategy 1: Answer the question that

you explored in Portfolio II to form an argument for Portfolio 3. For example:

If your research

question for Portfolio II was:

> Who is

responsible for intervening when child abuse is suspected?

Your

argumentative claim for Portfolio III might be:

> The

government needs to impose stricter laws to deter child abuse.

OR

> Teachers

need to play a more active role in preventing child abuse.

Strategy 2: Brainstorm possible

arguments by describing which parts of your issue you feel most strongly about.

Then, imagine that you were involved in a conversation surrounding these

aspects with some friends; what viewpoints might you offer? Which positions

would you agree/disagree with? What overall arguments would you make?

Discuss Audience and Context for Arguments: Use

this activity to model approaches to choosing a context and audience for the

first arguing essay. Ask two or three students to put their claims up on the

board (ask for volunteers - try pitching it as "free help" with their

essay). Then, check to see if these claims are narrow and debatable. If they

aren't, have students revise them to meet this criterion. If they are, use them

as models for argumentation. Ask the class to brainstorm a list of possible

audiences for each claim.

Use these points as a guide for this

discussion:

- Look

at the claim and ask - who needs to hear this argument?

- Who

would be most interested in this argument?

- Who

would be the most realistic audience to target (those who would actually

read it and be affected by it)?

- Discuss

how the argument would look differently based on each group of readers and

their various needs and interests.

- Where

might these different readers encounter this argument? Where would they be

likely to read about it? (If students have difficulty generating specific

contexts, tell them they'll need to do more research in this area to find

out which contexts are available. One way to do learn about contexts is to

look back at the journals they encountered when researching their issues

in Portfolio II. Also, tell them to do some topic searches to find out

where their issue is being talked about).

After discussing these points, shift the

discussion to an analysis of the Editorial page of the New York Times.

- Bring

in a few examples of the editorial and op-ed pages and discuss them

- What

shifts in thinking will you as a writer be required to do when considering

the well

- educated,

often urban, but largely inclusive audience of the Times?

Help students understand how to analyze a target

publication. They will need to select a publication to target for their

argument (If possible avoid general news sources such as TIME and Newsweek as well as the

Coloradoan, and the Collegian. A scholarly publication such as College English, various professional or

trade publication, even Web sites, would be better. Emphasize that you want

them to showcase their talents by selecting a publication that is unlike the Times

Editorial context they’ll use for the second arguing essay). To select an

appropriate publication, they should review and, ultimately, subject likely

candidates to a careful analysis. The results of the analysis will provide them

with enough information to help them determine whether the publication is

appropriate for their writing situation. A good place to start would be to

examine sources cited in the News and Issue Analysis. Analyzing the targeted

publication will also provide students with insights into the typical

organization, layout, and types of evidence used by articles in the

publication. When you assign the activity to help students conduct this

analysis, stress that they should also be aware of the use of visuals in the

publication, since graphics often play an important role in conveying

information and ideas to readers.

Assignment