The following is a print-friendly version of the Mon/Wed/Fri Syllabus.

To print the Tuesday/Thursday Syllabus, please see this page.

**Please Note: The Appendix portion of the syllabus is not included in this print-friendly version.

CO150--College Composition--is a common experience for most CSU students. The course or its equivalent is required by the All-University Core Curriculum to satisfy Basic Competency in Written Communication (see this description). In addition to meeting this CSU core requirement, CO150 credit will satisfy a core requirement for communication at any Colorado public higher education college or university. That's due to its inclusion in the state's guaranteed transfer (gtPathways) program (see this description, Written Communication).

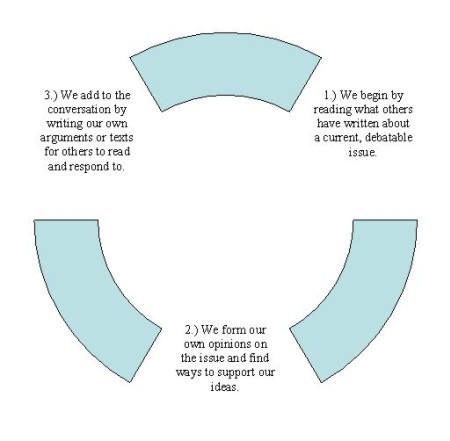

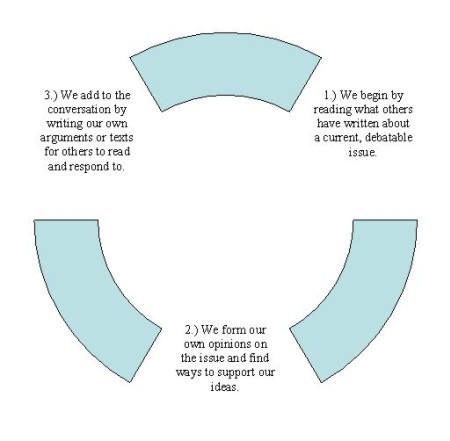

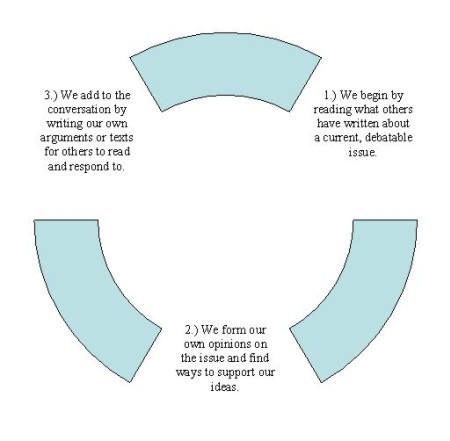

As we work toward these objectives, we rely on the metaphor of writing as a conversation. Like a conversation, writing involves exchanges of ideas that help us shape our own ideas and opinions. Students realize that they would be foolish to open their mouths the moment they join a group of people engaged in conversation—instead, they’d listen for a few moments to understand what’s being discussed. Then, if they found they had something to offer, they would wait until an appropriate moment to contribute. Our students understand what happens to people who make off-topic, insensitive, inappropriate or otherwise ill-considered remarks in a conversation. In CO150, we build on this understanding by suggesting that, prior to contributing to the debate about an issue, they should read, discuss, and inquire further about what other writers have written about it. Then, when they’ve gained an understanding of the conversation, they can offer their own contribution to it. By using this metaphor, we can help students build on their understanding of discourse as situated within larger social and cultural contexts.

With that notion in mind, we've structured the course in three phases. In Phase 1, students hone critical reading skills as they listen to the conversation on this question-at-issue: what should we eat? In Phase 2, students inquire into questions raised during the first phase, then add their voices to the conversation by writing an argument. In Phase 3, we begin new conversations about local sites of interest to new CSU students by investigating campus and community resources and writing an argument for a public audience about one. Each phase builds on the previous one to further develop the inquiry and composing competencies needed to achieve the course goals.

There are many approaches to teaching first-year writing. You may have experienced one of these other approaches as a student or as a teacher. Therefore, it may be helpful to consider what CO150 is not. It does not focus on writing about literature, creative writing or personal narratives. Nor is CO150 a course that teaches students how to write particular modes of discourse such as description, narration, or term papers. And while the course attends to editing and style concerns in the context of students' writing, it is not a grammar course. Rather, CO150 gives students experience with responding to various writing situations, making choices to address a variety of purposes and audiences, and developing strategies for successful communication.

The CO150 Fall 2007 Common Syllabus is designed to achieve the following course goals, which are aligned with gtPathways and AUCC guidelines:

The syllabus writers also hope this curriculum moves students toward these broader educational goals:

Phase 1: Reading for Critical Inquiry

In the first phase of the course, we're studying the work of an accomplished writer who addresses the question-at-issue: What should we eat? Michael Pollan is a professional writer and journalism professor whose writing for The New York Times exemplifies the thorough research, critical thinking and clear communication we ask our students to strive for. By looking at the strategies used by a writer who is trying to answer a significant question-at-issue as he approaches varying rhetorical situations, we hope to demonstrate critical inquiry-in-context that shares values and strategies with academic discourse. To this end, Unit 1 focuses on close and critical reading. We'll ask students to read several articles for various purposes, employing a variety of reading strategies. Our primary goal for this unit is to establish critical reading practices that will enable effective inquiry and support an understanding of writing as rhetorical practice. To assess students' close reading practices, we will ask them to write summaries of the readings. We'll assess students' critical reading practices with a review/letter at the end of this phase.

Phase 2: Expanding Critical Inquiry through Investigation and Argument

In the second phase of the course, we expand our inquiry into the question of what we should eat by identifying related issues, developing and refining questions, and investigating those questions. The goals for this phase include not only increasing our understanding of the issues, but also engaging in the conversations about them. In the first phase, we learned how one writer investigated the "ominvore's dilemma," considered some of the answers he found to "what should we eat?" and began posing further questions that Pollan's work raised for us. Now, we will refine some of those questions and investigate them. In the process of doing so, we will build information literacy as we find and select sources that offer a variety of perspectives on the questions we pose as well as credible and authoritative information. Students will work collaboratively to investigate one question and explain their findings to the class. These explanations can serve as initial inquiry for students who wish to pursue these questions further or as an impetus for initiating other lines of inquiry. Students will then join the conversation on a question-at-issue by writing an argument.

Phase 3: Sharing Local Inquiry with Public Audiences

In the final phase of the course, students will apply the inquiry and writing practices and strategies they have been using in the course as well as learn and develop additional research methods and writing skills. So far, we have focused our inquiry on questions related to “the omnivore's dilemma.” At this point, we hope students have begun to understand how critical inquiry into significant questions crosses disciplinary boundaries. As students investigate their issue across a variety of disciplines, we expect that they will learn to develop a repertoire of strategies for considering purpose and audience is a variety of academic writing situations. In Phase 2, students had a chance to see how conversations about significant issues occur in layered contexts that are interrelated, much like an ecosystem. Phase 3 asks students to explore the local ecosystem of the CSU campus and surrounding community, focusing on sites of academic, social, cultural, recreational, political, or personal interest to new students at the university. In this unit, we ask students to investigate a site of interest--a course, an academic program, a service, an activity, an organization—and explain the results to inform new students about it. Based on their investigation of the site and evaluation of its value to students, students will then write an argument to promote the site to other students, to address a problem with the site, or to effect change.

The following articles are assigned in the syllabus. A few alternatives are included, as well.

Waters, Alice, ed. "One Thing to Do About Food." The Nation 11 Sept. 2006.

Pollan, Michael. "An Animal's Place." New York Times 10 Nov. 2002.

---. "Cattle Futures." New York Times 11 Jan. 2004.

---."Mass Natural. New York Times 4 June 2006.

---. "Our National Eating Disorder." New York Times 17 Oct. 2004.

---. "Power Steer." New York Times 31 March 2002.

---. "The (Agri)Cultural Contradictions of Obesity." New York Times 12 Oct. 2003.

---. "The Futures of Food." New York Times 4 May 2003.

---. "The Modern Hunter-Gatherer." New York Times 26 March 2006.

---. "The Vegetable Industrial Complex." New York Times 15 Oct. 2006.

---. "Unhappy Meals." New York Times 28 Jan. 2007.

---. "You are What You Grow" New York Times 22 April 2007.

Accessing Articles

Web. All of the articles by Michael Pollan are posted in full on his web site: www.michaelpollan.com. There is no "printer friendly" or "text-only" option on the site, but the articles, but the articles do include the cover art from New York Times magazine issue in which they appeared.

eReserve. All above articles can be placed on eReserve in the library. Because they are all available in library databases, you can quickly and easily put them on reserve at your computer. Access for students is quite simple.

Library Databases. You and/or your students can easily retrieve all the articles from the Morgan Library site, using either the Citation Linker or directly from Lexis-Nexis or Academic Search Premier. You can assign students to retrieve the articles themselves. [handouts with directions for databases forthcoming from library]

Writing Studio File Folder. We have a preliminary assurance from the library that because your class's Writing Studio site is password protected, you may save articles you've retrieved from databases to the File Folder without violating fair use. Students can then download them from there in either PDF or Word format.

From the beginning, you need to make some decisions about your course policies regarding attendance, homework, late assignments, quizzes, and grades. Here are some suggestions:

Attendance: You should take roll at the beginning of every class. Devise a system to mark absences and excused absences. Many instructors use "A" for absent, and "X" for excused absence, and a check-mark for those present. The English Department may provide gradebooks in which you can record this information, or you may create a spreadsheet on the computer or adopt another method of your choice. The Writing Studio for your class also has an online gradebook. Establish at the start of the semester, and make crystal clear in your policy statement, what the consequences are for (excessive) absences and apply those equally to every student. Helpful hint: it is much harder, or nearly impossible, to toughen up later in the semester regarding policies; instead, it is to easier to lighten up. But always have your policies in writing so you can point students to them and rely on them for "back up" if the need should arise.

Late Attendance Policy: Particularly in early morning classes, students will push the envelope by coming in late. You can handle this through talking to the offenders, devising a policy where more than a specific amount of minutes equals an absence, whatever. Once you have policy, make it clear on your policy statement from the start of the semester and stick to it.

Collecting Homework: You have two choices here, and both methods have their merits. First, you can collect homework and Write to Learn (WTL) activities everyday. This obviously creates work for you everyday, but it also allows you to recognize right away who is having difficulty with certain skills, whether everyone really understood the reading, and how students are succeeding at creating accurate summaries or developing support, for example. (For the first three weeks of the semester, please collect all homework so you can determine whether all of your students should remain in CO150, should enroll concurrently in a Writing Studio tutorial, or should be moved to CO130. If you have a student whose writing suggests that he or she might be at risk of failing CO150, please email Sue Russell or Stephen Reid.) On these homework assignments, you do not need to comment extensively -- just a word or two of encouragement and/or suggestions. You might put an "S" for satisfactory work or a "U" for unsatisfactory work (if a student missed the point of the assignment) at the top. You could use an "M" in your gradebook if someone didn't hand in anything. It is also effective to assign numbers to homework assignments. Many instructors count homework assignments as 5 points each. It is a good idea to discuss how the points students receive correlate to their success on the assignment. For example, 4s and 5s may demonstrate an effective (or even great!) grasp of what the assignment called for, 3s may have gotten the point but need a bit of work, and 1s and 2s may warrant a visit to your office to clarify larger concerns. At the end of the semester, you can easily tally homework points and translate them to the percentage homework is worth in the students' grades.

After the first three weeks, you may wish to use the second method, and collect homework and WTLs only randomly and periodically. This saves you having to read every single thing they commit to paper, which has its obvious advantages.

We advocate the former method, though most people use the second. We find it helps us get to know the students better earlier, allows us to foresee problems, and students trust us more if we ask them to do something and then collect it faithfully. Some students will try to get away with doing as little as possible, and those students can get left behind if you're not keeping up with their work (or lack thereof).

The compromise is to collect homework everyday at first, to get them used to being responsible for it, and give it a quick read and a sentence or two. You can relax a bit after that (especially once you've got their major papers to read!)

Late Assignments: You should also anticipate how you will handle the occasions when students fail to turn in assignments on time. To prevent the majority of these occasions from happening in the first place, be very clear that it is each student's responsibility to turn in work when it is due, regardless of the circumstances that may surround their attendance at that particular time and/or date. Remind students that you have all due dates and assignments posted on your Writing Studio site. So if an athlete has an out-of-town softball game on the same day a major paper is due, make sure she knows she needs to send her work in with a trusted classmate or email it to you before she leaves. Also, be sure due dates and expectations are clearly explained for students well in advance and are accessible to them outside of the classroom (through assignment sheets, a syllabus, or an online course management calendar). However, "life happens" and some students may have legitimate reasons for why they miss a deadline. Establish the consequences for this early in the semester (and make them explicit in your policy statement) and apply these consequences fairly to every student.

Reading Quizzes: You do not need to give these; in fact, the syllabus doesn't include any. However, you may find students stop reading after a certain point or there is a particular day when clearly everyone felt the reading "wasn't important." Feel free to provide short quizzes, announced or unannounced, but decide beforehand how they will count: will they be part of the homework percentage? will they be part of participation?

Recording Grades in General: You will need to keep track of everything you take in since, undoubtedly at the end of the semester, a student will question you when you inform them they missed "X" homework or "Y" assignment. (It helps to email students several times during the semester who have excessive absences or who have not turned in homework so that they are aware of the number of classes they have missed and know what the consequences will be. Construct a system to record not only essay grades but also homework assignments, write-to-learns, workshop days, any quizzes you might give, etc. No matter what system you devise, be sure to label the assignments, papers, homeworks, etc. clearly enough so that two months later you'll know what each label refers to.

In the first phase of the course, we're studying the work of an accomplished writer who addresses the question-at-issue: What should we eat? Michael Pollan is a professional writer and journalism professor whose writing for The New York Times exemplifies the thorough research, critical thinking and clear communication we ask our students to strive for. By looking at the strategies used by a writer who is trying to answer a significant question-at-issue as he approaches varying rhetorical situations, we hope to demonstrate critical inquiry-in-context that shares values and strategies with academic discourse.

Pollan's writing engages us in answering an enduring and significant human question--What should we eat? He relies on firsthand reporting as well as his reading from agriculture, food science, history, and other disciplines. His New York Times articles show us how a writer pursues a question-at-issue, synthesizes what he learns, and presents arguments for ethical and healthful eating. In this way, his work is an example of a form of discourse highly valued in academic contexts. By focusing on Pollan's articles, we can examine with students how a successful writer engages in critical inquiry and communicates the results to critical readers.

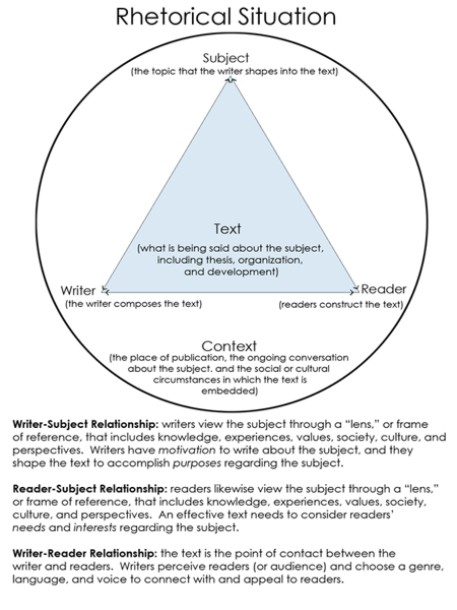

To this end, Unit 1 focuses on close and critical reading. We'll ask students to read several articles for various purposes, employing a variety of reading strategies. Our primary goal for this unit is to establish critical reading practices that will enable effective inquiry and support an understanding of writing as rhetorical practice. The following writing assignments and class activities are designed to teach and assess such reading practices.

We start with close reading of texts to practice strategies for accurate comprehension of information and arguments. For our purposes, close reading will include identifying arguments, clarifying information and recognizing rhetorical strategies. We will ask students to read a series of short articles from the Nation by various authors and three New York Times magazine columns written by Michael Pollan, all of which address the question: What should we eat? Our purpose for reading these pieces is to learn how various writers address the question-at-issue. To assess students' close reading practices, we will ask them to write summaries of the readings.

After reviewing close reading strategies and discussing various responses to our question, we will continue our inquiry by employing critical reading strategies as we read three longer pieces by Pollan from the New York Times magazine. These articles deepen inquiry into the social, cultural, ethical and environmental consequences of American eating. As we continue inquiry into our question-at-issue, we want to sharpen critical tools for not only understanding Pollan's arguments but also for analyzing, evaluating and responding to them. We hope to engage students in examining how one writer presents the answers he found to the question through research and critical thinking. By analyzing and evaluating the effectiveness of Pollan's writing, students can continue inquiry into the question (through making decisions about information and posing further questions). In addition, students will be introduced to writing as rhetorical practice by examining how Pollan's articles address the rhetorical situations in which he wrote them. We'll assess students' critical reading practices with a review/letter at the end of this phase.

By the end of Phase 1, students should be

Overview. Students write summaries in college classes for a variety of purposes, including allowing instructors to assess students' understanding of texts. We will practice this important kind of academic writing in this assignment.

Purpose. Your purpose in writing a summary of an article is to demonstrate to your instructor that you have read the article closely. You will need to retell, objectively and concisely, the writer’s argument (thesis and reasons).

Audience. Your CO150 instructor. Your reader is, therefore, very familiar with the article. She will expect that your summary is accurate and objective, and will know if it is not.

Subject. Choose one of the following New York Times articles by Michael Pollan to summarize:

Strategies. To achieve your purpose with your audience, use these strategies.

Details.

Format: [Instructors, add your formatting requirements here. Typically, instructors ask that the summary be double-spaced, with a readable 11- or 12-point font, with reasonable margins, etc. Also, indicate what identification you want from students (name, date, course #, etc.)]. Turn in your summaries with other materials specified in class.

Length: about 1 double-spaced page

Worth: 5% of your final course grade.

Due: Beginning of week 3

Grading Criteria

Your instructor will ask these questions as she grades your summary. They are listed in order of importance.

Purpose/Audience: Does the summary convince the reader that the writer has read the article closely and understands its argument?

Conventions: Has the writer observed the genre conventions of academic summary?

Summary grades will be assigned as follows.

An “A” summary will convince your reader that you have read the article closely and represent its argument well. It will not only accurately and objectively report the argument, but will focus on the article’s purpose and how the argument supports that purpose. “A” summaries rely mainly on paraphrasing but will quote key words, phrases and/or sentences effectively. The reader of an “A” summary will always be aware that the summary refers to the article because it contains frequent and varied author tags. “A” summaries will be clear and readable without distracting editing errors.

A “B” summary will also convince the reader that you have read the article closely and represent its argument well. B summaries, however, will show that the writer needs to work on communicating information more effectively. These summaries will report the thesis and reasons of the argument but could organize them more effectively. “B” summaries may also need more work on balancing quoting and paraphrasing and/or attributing information. They will be clear and readable but may need further editing for minor errors.

A “C” summary will show the writer is learning to read closely and to summarize but has more work to do achieve all of the goals of the assignment. “C” summaries will be generally accurate, though they may contain minor misreadings. These summaries may contain subjective responses to the article as well as objective information. They will show an effort to focus on the argument, but may get sidetracked by giving too many details. A summary that reports information accurately but does not effectively represent the argument will also receive a C. These summaries might need stronger organization to show how the argument’s reasons support its thesis. “C” summaries may also need more editing for readability.

A “D” summary shows an attempt toward the assignment goals that has fallen far short. These summaries will show significant problems with close reading and will not communicate effectively. “D” summaries contain serious misreadings and inaccuracies. They may not focus on reporting the argument at all but instead list information from the article. The reader of a “D” summary is convinced that the writer has only a slim grasp of close reading and summarizing. These summaries often need editing to be clear.

An “F” summary ignores the assignment, or is unreadable due to language and coherence problems, or shows little to no understanding of the article or summarizing, or is plagiarized, or is not turned in.

Overview. When we're involved in meaningful inquiry, we often want to discuss what we're discovering and the questions our research raises. If we get really excited about a topic we're investigating, we want to get others interested in it. This assignment asks you to initiate a critical conversation with someone you know about the articles we've been reading by writing a letter. Its goal is to extend the conversation we've begun about "the ominvore's dilemma."

Purpose. The main purpose of your letter is to start a discussion with your reader about an article. You will need to inform your reader of the content of the article and convince them that the article is worth discussing critically.

Audience. You will choose the recipient of your letter. Choose a person who is interested in the topic or issues of the article, whom you know reasonably well, and who would have knowledge or experience of the issue(s). Teachers, professionals from various fields, and people with direct experience related to the topics/issues (in agriculture, vegetarianism, activism, etc.) will make the best choices of readers. Just be sure to choose someone who not only would be interested in the subject but who also might have a perspective about it that would help you understand the issues better. You will have to assume that your reader has not read the article.

Subject. Choose one of these articles by Michael Pollan from the New York Times:

Author. Present yourself as someone who has read Pollan's article closely and critically. Show your interest in discussing issues from the article thoughtfully and in coming to a broader and deeper understanding of those issues.

Strategies. To achieve your purpose with your audience, use these strategies:

Details.

Format: Use a standard letter format by beginning with date, a salutation (Dear _____) and ending with a closing (Sincerely, Your friend, Cheers,) and signature. Print your name under the signature. Double space the letter. Turn in your letter with other materials specified in class. (Letters to a family member or close friend will have a less formal format.)

Length. Three-four (3-4) ds pages.

Worth: 15% of course grade.

Due: Beginning of week 6.

Grading Criteria

Your instructor will ask himself these questions as he grades your letter. They are listed in order of importance.

Purpose/Audience. Does the letter identify and address its intended reader? Does it engage its writer and reader in a critical conversation on "the omnivore's dilemma"?

Conventions. Does the letter observe conventions of academic discourse that will enable a critical conversation with your reader?

Grades for the letter will be assigned as follows.

An "A" letter will convince your intended reader (and your instructor) that the article you chose is worthy of a critical discussion that furthers inquiry into "the ominvore's dilemma." These letters will show that you not only understand and represent Pollan's argument well but also can have a critical conversation about it. "A" letters will consider what Pollan's article has to say about eating in America, evaluate his contribution, and raise additional questions for further inquiry into the subject. These letters will not only inform their intended readers about Pollan's article but will also show readers how reading it can help them learn more about the question-at-issue. "A" letters focus on explaining why you recommend the article and are organized to highlight and explain reasons for your recommendation. "A" letters will show a good sense of purpose, audience and conventions and will be carefully edited for readability.

A "B" letter will also convince your audience that the article you chose is worth reading and discussing. These letters accurately and objectively represent Pollan's article, and they explain why it's worth reading. However, they need additional development to explain how the article contributes to inquiry into the question-at-issue or they could be more effectively organized. These letters may need more editing, but will be clear and readable.

A "C" letter but will show that the writer is working toward the assignment goals but has not entirely achieved them. In general, "C" letters will have problems developing an argument for how reading the article can lead to a critical discussion of the article. For example, a "C" letter may need a stronger focus on making and supporting the recommendation, more development of support for its recommendation, or more effective organization to convince the reader. Though they may have some minor inaccuracies, these letters will generally represent the article well. "C" letters may also need to observe conventions more closely.

A "D" letter will show an attempt to meet the goals of the assignment that falls short of doing so. A "D" letter has significant problems with critical reading and/or communication that prevents you from achieving your purpose with your audience.

An "F" letter ignores the assignment, or is unreadable due to language and coherence problems, or shows little to no understanding of the article or of critical reading, or is plagiarized, or is not turned in.

The following lesson plans are designed to demonstrate effective pedagogy for achieving CO150 course goals. Their primary audience is new teachers (or teachers new to CSU's composition program).

Phase 1 Lesson Plan Template

Below we have described the format we have followed in writing lesson plans for this syllabus. As the semester progresses and you take more ownership of your class you'll probably find ways of altering this template. We encourage you to do that when you feel comfortable--from the very start, you should customize the lesson plans in this syllabus so that the design is readable for you during class and so that you have conceptualized the lesson from start to finish.

Lesson Objectives

This is the overview of what you want to accomplish for the class session, i.e., what students should know or be able to do as a result.

Connection to Course Goals

Here, we've articulated the ways in which the class activities help lead us to accomplishing course goals. It's easy to overlook this step in favor of getting to the "to-do" list of activities, but taking time to articulate the connection to course goals can help you refine your plans, transition between activities, make decisions on the spot, and feel more confident in knowing why you are teaching what you're teaching.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing (CSOW)

In this section, we have explained the ways in which the class session is designed to be relevant to student writing. Students appreciate how CO150 class time always contributes (in some way) to a graded writing assignment.

Prep

Here we've explained the things you'll probably need to do to prepare for class.

Materials

Here are the things you'll need to have with you in class. We've left the everyday stuff (like chalk or markers, attendance sheet, etc.) off.

Lead-in

In this section, we discuss the ways in which the previous class session(s) and students' homework have set up today's class.

Activities

This is the list of things you'll do in class, including handouts, text for overhead transparencies, homework, and more. For the first few weeks we've included introductions, transitions, and conclusions in each lesson plan to guide new teachers. Soon you'll get used to that "scaffolding" enough that you'll write your own.

Connection to Next Class

Here we've shown some of the ways in which the lesson leads into the next.

Day 1 (Monday, August 20)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

Today's class introduces students to course goals, content, and structure, as well as their instructor and each other.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Introducing students to each other and to the course lays the groundwork for the Phase 1 writing assignments.

Prep

After orientation last week, you're well prepared to teach your first class (even if you feel like you're not!). To get ready for day 1, reread the syllabus introduction, revisit the first few readings you'll assign, prepare your materials (see the list below), ask for any advice, help, etc. you need (the lecturers are here for you!), and write out your own lesson plan (do this even if you plan to follow this one 100%--the act of writing it out in your own words and in a format that makes the most sense to you will give you confidence and will help you remember what you want to do, and why).

Materials

Class roster (as up to date as possible)

20 copies of your syllabus (if Writing Studio instructions aren't on your syllabus, prepare an extra handout with those)

Yellow handouts about the CO150 drop policy

Overhead transparencies:

Instructions for student introductions

Homework

Lead-In

Some students may have prepared for class today by buying the textbook. Also some may have set up Writing Studio accounts. Today is unique because it's a fresh start. Your students will come in with few ideas about what the class will be about, what the atmosphere will feel like, etc. One of your primary tasks for today is to establish a classroom culture that will work for you and your students, and to give students a fair idea of what they can expect for the rest of the semester.

Activities

Before class begins, write your name, the course number, section, and title on the board. Once all (or most) students have arrived, take a moment to introduce yourself--tell students what you would like them to call you, and consider what else you'd like them to know about you. The formality of your introduction will help set the tone for the semester, so consider the atmosphere you want to foster. It's much easier to become less formal as time goes on than it is to become more formal. Make sure everyone is in the right place--have students check their schedules to be sure that they're really in your section. Offer an "out" for anyone who is in the wrong room.

Use your roster to call names and make note of anyone who is absent. After you have called all the names on your list, ask if there is anyone in the room whose name you didn't call. If anyone raises his/her hand, take time to sort it out. Possible reasons why the student isn't on your roster include (in order of likelihood):

Transition It's important to articulate a connection between each activity so that your classes feel well-planned and organized and, even more importantly, so that your students understand the purposes of the activities you ask them to do. Over time, you'll get good at transitioning without thinking about it. You may already be good at this; one way to ensure that you use transitions, and to help you speed to transition-use stardom, is to write them out in your lesson plan. Over time, you can scale this back, but at first it's a really good idea to think through transitions ahead of time. Here, you can simply say something like: now that we know who is here, let's take a look at what this class will be about.

Spend time looking at the document with your students. Discuss the course description, your contact information, your grading system, and key course policies. You might not discuss every single thing in detail; if you don't (and even if you do), remind students to reread the document after class and to email you with any questions or concerns.

Transition Here you might say, we'll be doing a lot of work together in this course so let's start to get to know each other now.

Choose one of the introduction activities below, or use another that accomplishes the goal of allowing students to make connections with each other and the goal of setting precedents about participation and community.

Option 1:

In this activity, students pair up and interview each other; then they introduce each other to the rest of the class. Here are instructions which you can put on an overhead (be sure to enlarge the font to 16pt or larger):

Introductions

Pair up with someone seated near you (preferably someone you don't already know).

Take a few minutes to find out interesting things about your partner---you can ask the typical questions (name, major, hometown, etc.) but also try to find out something unusual, unique, silly, amazing, etc. so that we can start to learn about each other.

In a few minutes, I'll ask you to introduce your partner to the class, so be sure to jot down notes.

Option 2:

In this activity, you generate a handful of questions with the class and then go around the room and allow each student time to answer the questions. You can start out with the obvious--write "What's your name?" on the board. Ask the students what else they'd like to know about each other. Give them time--if nobody suggests anything, make another suggestion. Something like "What's your major?" works and might get them going with more suggestions. Once you have four or five questions listed, end with one of your own---something like "what did you have for dinner last night?" or "what's your favorite food?" can help connect this activity to our question-at-issue. Feel free to answer the questions yourself, too, if you'd like.

No matter the option you choose, keep track of time--it's easy for some students to get carried away. You need about 5 minutes after this activity to finish up with class. If you're running out of time, cut the activity short and finish it on Wednesday.

Transition Here you might say, now that we've met each other and learned some things about the course, we're ready to proceed with a great semester.

Put the homework on an overhead transparency, explain it, and allow students time to copy it down (as an alternative, you can make handouts; you can print 4 or 5 to a page and cut them apart to save paper and precious copies. If you worry about running out of time, or that students may not get everything copied down correctly, handouts are a good option).

Homework for Wednesday

- Log in to our class page at https://writing.colostate.edu. Instructions for how to do this are on the syllabus.

- From our class page, go to the File Folder and open the document called "One Thing to Do About Food."* Print this document out (it's very important that you have hard copies of our readings with you in class) and read it. For each essay, find a sentence (or two) that encapsulates the main idea of which the writer aims to convince us. Underline the sentence and/or write it out on a separate sheet. Do the other things you tend to do when you read closely (underline key passages, write questions and reactions in the margins, etc.). Bring this document to class with you on Wednesday.

- Be sure that you have purchased your textbook by Wednesday.

*These directions represent one method of making articles available to students: putting copies of them in the File Folder of your Writing Studio class page. Students may also retrieve articles from www.michaelpollan.com or through Morgan Library databases. See appendix for a student-ready handout with directions for retrieving articles from library databases.

Wrap up today's class and point students forward to Wednesday's class.

Be sure to always conclude class, even if you are pressed for time. Here you might say, it was great to meet all of you today; I'm looking forward to discussing the reading with you on Wednesday.

Connection to Next Class

Today you've taken care of a lot of "business" and you've prepared students for what they can expect next time. On Wednesday, you'll introduce students to academic inquiry and the question-at-issue.

You might take a moment to reflect on today's class, to assess what went well and what could have gone better (and go easy on yourself--you're probably way more aware of what you did or didn't say/do than your students are!), and to make notes about anything you need to remember for next time. Be sure to check email now and then before Wednesday so that you can help students out with questions, Writing Studio issues, etc.

Day 2 (Wednesday, August 22)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

Today's class focuses on close reading and begins to introduce rhetorical concepts.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Identifying thesis statements practices close reading and prepares students for summary writing. Developing questions for further inquiry will engage students in ongoing inquiry that they will write about in Phase 1 and Phase 2 assignments.

Prep

Before today's class, be sure you have reread "One Thing to Do About Food,” revisited the Writing as a Conversation model and written your own lesson plan.

Materials

"One Thing to Do About Food" (annotated for each author's thesis and reasons)

Overhead Transparencies:

Identifying Thesis Statements activity instructions

Homework (or make handouts for homework--do the same thing that you did on Monday)

Lead-In

For today's class, students have read "One Thing to Do About Food," have looked for thesis statements, and are expecting to discuss the reading. Note that it's not uncommon at all to have a few students come to class the second day without having done the homework. Usually this is because of technical difficulties that the students have waited until class to tell you about. Any unprepared student can join with a peer to look on with the reading and will be able to follow along during class. Be sure to arrange a way to help the student with the problems and point out how important it is to keep up with everything. Remind students of the upcoming limited add/drop policy deadlines. Refer them to the yellow sheet you handed out on the first day.

Activities

If you arrive to class a few minutes early, you might write the "agenda" on the board. A brief list of today's activities could go something like: "Discuss reading; Identify thesis statements; Introduce summary; Further inquiry." If you do this, make it a routine so that students know what to expect.

Take care of any remaining registration issues, and be sure to note which students are absent.

Begin today's class by previewing the activities you have planned: today we are going to start talking about academic inquiry and the subject we'll be inquiring into together over the next several weeks-- food ethics.

Prepare an overhead transparency with instructions:

Write-to-Learn

On a sheet you can turn in, please write for a few minutes in response to the following questions:

- Are there problems with food in the U.S. today? If so, what are some of them? If not, why are so many people concerned about food right now?

- What are some of the problems with food in other parts of the world?

- What are some ethical (right/wrong) debates about food?

- Do you have an answer for "what should we eat?" If so, what is it? If not, why not?

When students have finished writing, engage them in a brief discussion of their responses. Then collect the Write-to-Learns. You'll want to read them over to get a preliminary sense of your students and their writing as well as to start a list of inquiry questions and topics.

Transition: We've come to this class with our own knowledge, beliefs and values about food, and we've read what several writers think about the issue. From this starting point, we'll explore the subject together.

Explain to students that as members of the academic community, one of our goals is to inquire into significant questions. Working together, we can see what others have to say about such questions and find "answers" to them. Explain the inquiry list. Here’s a sample explanation:

As we work over the next few weeks, we will be keeping track of the questions and terms we want to know more about. I will start a list as I read your WTLs from today. During each class session, someone will be in charge of adding questions to the list rasied by our reading and discussions.

Then ask for a volunteer “list-keeper” for today (or start with the first (or last) name on your roster). The "list-keeper" should listen especially carefully during discussions to make a record of the ideas and questions that come up. Also, the list-keeper can add questions of his/her own.

Transition: one of the ways we will inquire is to discuss what we are reading.

Talk with your students about the reading. While the aim of this activity is to teach students what it means to read a text closely, it's very likely that students will have reactions and opinions they want to share. You might start off with a general question, such as "which writer did you agree with most?" or "which of these suggestions do you think would work best?" As students offer answers, encourage them to talk to each other by responding with questions like "how many people agree (or disagree) with that?" or "who had a different reaction?" Don't hesitate to ask "why" or for clarification. If your students are very reluctant to speak, give them a WTL and then ask for some responses. If your students are overly-exuberant, keep track of time so that you can move forward with class after 10 minutes or so.

Transition: these reactions show that, often, writing gets a conversation going.

Explain the ways in which writing is similar to conversation. Here’s a sample explanation:

Like a conversation, writing involves exchanges of ideas that help us shape our own ideas and opinions. It would be foolish to open your mouth the moment you join a group of people engaged in conversation—instead, you listen for a few moments to understand what’s being discussed. Then, when you find that you have something to offer, you wait until an appropriate moment to contribute. We all know what happens to people who make off-topic, insensitive, inappropriate, or otherwise ill-considered remarks in a conversation.

The following is a visual representation of the way in which this course is designed around the writing as conversation metaphor. Present it to students on an overhead, or draw it on the board.

Right now, we are at the first stage: reading what others have written. That is, we are listening in on the conversation.

Take time to define "thesis statement." There are many ways of defining this term; for our purposes a definition such as "the main idea that the writer wants to communicate to readers" works well.

How can a reader find a thesis statement? Brainstorm ideas.

The writers in "One Thing to Do About Food" have made their thesis statements pretty easy to find, because each essay focuses on answering the question: "What is the one thing we can do about food to make the most difference in current food-related problems?" Practice with Peter Singer's essay--what is his answer to the question? (He says, “don’t buy factory-farm products.”)

Now, give students a chance to practice this in small groups. Give instructions for group work on an overhead before you divide students into groups.

Identifying Thesis Statements

Work with your group to identify the thesis statement in one of the "One Thing to Do About Food" essays.

If you disagree, try to figure out why, and try to reach a consensus.

In a few minutes, you'll report your findings back to the class.

Group 1-Schlosser

Group 2-Nestle

Group 3-Pollan

Group 4-Berry

Group 5-Duster and Ransom

Group 6-Shiva

Group 7-Petrini

Group 8-Hightower

Have students count off from 1 through 8 to create groups (all 1’s will group together, all 2’s together, and so on). Direct groups to particular parts of the room. Give groups a chance to say "hello" to each other, and then remind them of the task at hand.

It probably won't take groups a lot of time to do this; ask the first two groups finished to come to the front of the room and write the thesis statement they came up with on the board.

Once you have two theses on the board, talk them through with the class. Ask groups to explain why and how they identified this particular thesis, and ask the class if they agree with this group's identification. You can refer to your own notes to add on to (or to correct, if needed) what the groups have come up with. Remind students that thesis statements don't always come in the first paragraph, nor are they always neatly packaged in one obvious sentence.

Transition Being able to find the writer's thesis statement is essential to listening to what the writer has to add to the conversation on an issue.

Assign the following as homework:

Homework for Friday

- Read pages 163-168 in The Prentice Hall Guide for College Writers (PHG).

- View the video titled “The Meatrix” (available through the links section of our class page) and the accompanying presentation (available in the file folder).

- Annotate "One Thing to Do About Food" to identify reasons that support each author's thesis.

Conclude class by saying something like, on Friday, we will work on identifying how these writers support their thesis statements and work on writing summaries.

Connection to Next Class

On Friday, you will continue on with concepts you introduced today and introduce academic summary. In class, you will review summary writing, and students will work collaboratively to write summaries of the arguments in "One Thing to Do About Food."

Day 3 (Friday, August 24)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

Today's class focuses on close reading and begins to introduce rhetorical concepts.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Writing collaborative summaries gives students practice with summary writing, the focus of our first graded assignment.

Prep

Before today's class, be sure you have reread "One Thing to Do About Food," added to the "inquiry list" owithquestions and terms from Wednesday's WTL's, reviewed the PHG reading and "The Meatrix" PowerPoint, and written your own lesson plan.

Materials

Inquiry List

"One Thing to Do About Food" (annotated for each author's thesis and reasons)

Overhead Transparencies:

Group Summary Activity instructions

Homework (or make handouts for homework--do the same thing that you did on Wednesday)

6 blank overhead transparencies (you can get these from the mailroom in Eddy)

6 overhead markers, such as Vis a Vis (you'll need to supply these yourself)

Lead-In

For today's class, students have reread "One Thing to Do About Food," looking for reasons to support each thesis statements, and are expecting to discuss the reading. They have also viewed the PowerPoint about summarizing and have read about summaries in the PHG.

Activities

Write the agenda on the board if that’s what you’ll prefer to do throughout the semester. From here on out, the lesson plans in this syllabus won’t include this item, so remember to add it to your own lesson plans if you will be using it.

Take care of any remaining registration issues, and be sure to note which students are absent.

Ask students to sit with their groups from Wednesday.

Begin today's class by previewing the activities you have planned: today we will practice demonstrating close reading by writing summaries.

We ask students to write summaries that demonstrate their accurate comprehension of the texts. Writing a summary requires one to set aside one’s own biases and preconceived ideas and really listen. The summaries that students write will enable us to assess their ability to distinguish between subjective reactions and objective understanding of what a text says.

Introduce academic summary by explaining the above in your own words. On the board, write:

Academic Summary

Purpose: to offer a condensed and objective account of the main ideas and features of a text; to demonstrate your accurate comprehension of a text

Audience: your instructor

Make sure students understand what "objective" means, and then ask students to talk about how they might go about writing a summary that accomplishes the above purposes for the audience. That is, how can students write a summary that will show you, the instructor, that they have understood what they have read?

This is a key moment of learning for students. They're probably used to being told how to write a particular kind of document. Give them time to think through your question, and be encouraging about even minor suggestions (provided they apply--if a student says "write about why I disagree," for example, you don't want to validate that because it will confuse everyone in the class). Below "Purpose" and "Audience" on the board, make a list of "Strategies." Once students have offered everything they seem to have, take time to assess the list of strategies. If there's anything that seems off, clarify it. If anything essential is missing, add it and explain why you are adding it. It's ok if this list isn't 100% complete because students will read more about writing summaries for homework, and you will cover it more in class next week. You may want to refer to "The Meatrix" PowerPoint lesson on summarizing as you prompt students here. In a perfect world, the following would be on the list in some form (explanations you might give are in parentheses):

Choose one of the essays in "One Thing to Do About Food" and model the process of summary writing for students. Start with the thesis, and then help students identify key points. Here's an example from Peter Singer's essay:

Start by writing "Peter Singer, ‘One Thing to Do About Food,’ The Nation, and September 11, 2006" on the board.

You've already identified the thesis: "don't buy factory-farm products." Write this on the board, and then introduce the concept of "key points."

Often, key points are reasons, or "because" statements that support the thesis. Sometimes they are not phrased with the "because" conjunction, though they could be. Ask students to find particular language in Singer's essay that explains why he thinks we should not buy factory-farm products. Possibilities include: "Factory farming is not sustainable," it is “the biggest system of cruelty to animals ever devised," factory farmed animals have lost "most of their nutritional value," and factory farming "is not an ethically defensible system of food production."

How do these statements differ from ones like "pig farms use six pounds of grain for every pound of boneless meat we get from them" and "pregnant sows are kept in crates too narrow for them to turn around"? The difference, mainly, is in scope--the statements quoted in the paragraph above are broader and use general language; they are reasons. The statements quoted in this paragraph are narrower and give specifics; they are evidence for the reasons. A way to determine whether or not a statement is a reason or if it is evidence is to see if it can be grouped with other similar statements in the essay. Singer includes a few more statements about feed for animals--see paragraph 3. He includes other statements about animals' quality of life--see paragraph 4. Writers often offer several pieces of similar evidence to prove a reason; Singer has done so in this essay.

With a thesis and some reasons listed, you’ve got a good start. But does this cover all of Singer's main points? Not really; arguments often contain more main points than just a thesis and reasons (sometimes they offer concessions, refute counter arguments, or suggest solutions. These things do not offer direct reasoning for the thesis, but still they are integral parts of the argument). In Singer's case, he has included an alternative to his thesis: he says that the best thing we could do would be to "go vegan," or at least vegetarian. This is another key point, though it is not a reason for the thesis (saying "We should not buy factory farm products because we should go vegan" doesn't make logical sense). Leaving this point out of the summary altogether, though, would be misrepresenting the text.

On the board, now, you should have the basic things that would need to go into a summary of Peter Singer's essay. Ask students how they would turn this list into paragraphs. How long might the summary be? Might you incorporate quotes?

Transition Since I'm asking you to write a summary for homework, I'd like to give you a chance to practice writing one here in class.

In this activity, students will work in their small groups to complete the same tasks you just worked through on the board, and to write the summary in paragraph form. They should continue on with the same essay they used in Wednesday’s activity. Explain the group work instructions (on an overhead transparency) and then give groups time to work.

Group Summaries

Work with your group to write a summary of one of the essays in "One Thing to Do About Food":

First, read the essay closely and make an outline like the one we just did together

- Identify the author, title, magazine, and date

- Identify the thesis

- Identify the reasons/key points

Then, come up to the front of the room to get a blank transparency and an overhead pen.

Write an academic summary in paragraph form. Please write your summary on the overhead transparency so that we can look at it next week during class.

Circulate around the room to answer questions and to keep track of how much time the groups will need. You need a few minutes after this activity to assign homework. Once all (or most) groups are finished, collect the transparencies and markers. Talk about the writing process, and ask if students have questions about writing summaries.

Transition:

For homework you have a new article to read and summarize--this one is by Michael Pollan (the author who wrote about the farm bill).

Assign the following as homework:

Homework for Monday

- Access, print and read “Our National Eating Disorder” by Michael Pollan [remind students where/how to get it]. Use close reading strategies as we discussed in class.

- Using your notes from today’s class as well as the summary example and guidelines on pages 164-168, draft a summary of Pollan's article. Print out your draft and bring a copy of it to class with you on Monday.

Conclude class by saying something like, next week we will continue with our work of academic inquiry by working more on summary and by generating inquiry questions as we talk about Michael Pollan's work.

Connection to Next Class

On Monday, you will continue on with concepts you introduced today. Identifying a writer's argument will get more complex as we ask students to read more complex articles, so you'll need to spend more time with that. Students will be self-evaluating their summaries on Monday as well; to model that, you can use one of the groups’ summaries from today's class.

Day 4 (Monday, August 27)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

Today, students continue to practice close reading as they learn to recognize strategies writers use to accomplish goals and connect with audiences.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Practicing close reading will help students write effective summaries. Self-workshops encourage students to look at their own work critically in order to revise.

Prep

Decide how you will prefer to keep your attendance record from here on out (you shouldn’t have any more roster changes), and set up what you need in order to do that. Also, decide how you will hold students accountable for reading—quizzes? WTLs? another activity? You don’t have to do the same thing every time, but be sure you do something, especially at first, so that students do the reading. Reread “Our National Eating Disorder” and your own summary of it from GTA orientation. Make sure you have notes about what needs to go into a summary of this article. Make your own adjustments to the summary criteria and the assignment sheet as well.

Materials

Inquiry list

Attendance record

“Our National Eating Disorder” (annotated)

Your notes on and summary of the article

Summary assignment sheets

Overhead transparencies:

Quiz questions or WTL prompt

Summary criteria

Self-workshop instructions

Lead-In

For today’s class, students have read “Our National Eating Disorder” and they have drafted summaries. They are expecting to discuss Pollan’s piece and their summaries. Since Pollan’s article is more complicated than the “One Thing to do About Food” essays from last week, and because summary writing may be new to many students, students might be coming to class today with questions and uncertainties.

Activities

After today’s class you should not have any roster changes, so you can begin to take attendance in the same way you’ll take attendance throughout the semester. Be sure to keep an accurate record so that you can apply your attendance policy fairly. Keeping accurate attendance records is essential. If you end up lowering a student’s grade for excessive absences, you must have accurate records of the classes missed.

Introduce today’s class by designating a student to be in charge of the inquiry list today. Link back to last week (last week, we began to inquire and to learn about summary writing for example). Preview the activities you’ll do today.

Allow students time to talk about the homework by asking questions such as:

Transition The articles we are reading this week are considerably more complex than the essays we read last week, so we’ll be sure to take time to understand what they say.

Take plenty of time to discuss what Pollan says in “Our National Eating Disorder.” Here you’re modeling what you are asking students to do for the first assignment, so it’s important that you talk it through so that students see how a more complex argument can be structured.

Start by brainstorming ideas on the board. What does Pollan say? Here, anything that is objective and accurate (even if it is a minor point, evidence, etc.) is worthwhile. Write student responses on the board (or ask a student to be your “scribe”).

Once you have most or all of Pollan’s major points on the board, begin to label them: thesis, reasons, evidence, key points (such as counterarguments, questions-at-issue, causes and effects, solutions, etc.).

Here’s an example of how a class might brainstorm “Our National Eating Disorder.” On the board, you can shorten student responses.

What Pollan says:

Allow yourself time to look through your own notes to see if there is anything to add to the list your students develop and then allow students another opportunity to add anything more.

Finally, determine what should go into a summary in order to accurately and objectively represent Pollan’s argument (you really can’t go overboard in reminding students of the purposes of summary writing). It’s tempting to summarize in chronological order (Pollan says X and then X and then X, etc.), but that doesn’t enable one to restate the argument. Take time to determine Pollan’s thesis first. As with the essays from last week, Pollan does not announce his thesis in his first paragraph.

One way to do this is to label the items in the list as part of the thesis (you can write “thesis?” next to any items up for debate), as reasons, as key points (you can specify what kind of key point it is), and as evidence.

As you talk students through these decisions, you don’t need to “give them the answers.” That is, you don’t need to write out The Thesis on the board for them, in part because that would be doing the work you want them to learn how to do. More so, though, because there is not just one way of stating Pollan’s thesis. Though we ask students to be objective in the summary, identifying and rephrasing the thesis is, to a degree, an interpretive act that can’t be 100% objective. Here are several acceptable ways of phrasing Pollan’s thesis:

Americans have a paradoxical relationship to food which has made us “the world’s most anxious eaters.”

Michael Pollan says that America’s scientific approach to making decisions about food has created a culture of anxious, guilt-ridden eaters who, while “obsessed” about health are really quite unhealthy.

According to Michael Pollan, Americans need to change their attitude towards eating from a paradoxical one to one that balances health and pleasure.

Talk about how Pollan supports his thesis, being sure to sort out confusion about key points vs. evidence. Refer back to the explanations in last week’s lesson plans for ways of helping students discern the difference.

Give students a chance to look through their own summaries to make notes of things they might add or remove (more opportunity for this later, too).

Transition the most important thing you can do in your summary is accurately and objectively represent the writer’s argument. Let’s look at the other criteria now.

Remind students of a summary’s purpose and audience as you present the following on an overhead transparency:

Purpose/Audience: Does the summary convince the reader that the writer has read the article closely and understands its argument?

- Accuracy: Does the summary accurately represent the author’s thesis and reasons/key points? Does the summary contain misreadings? Does the summary omit key elements of the article?

- Objectivity: Does the summary remain focused on fairly retelling the author’s main ideas? Has the summary writer included anything subjective (such as reactions, judgments, etc.)? Has the summary writer included minute details in addition to or in place of larger points?

Conventions: Has the writer observed the genre conventions of academic summary?

- Attribution: Does the summary cite the author, title, date and publication of the article? Does the summary writer use author tags so that it remains clear that he/she is retelling the author’s ideas?

- Quotes and Paraphrases: Does the summary contain both paraphrases and quotes? Are the paraphrased and quoted passages appropriately chosen? Are they well integrated into the summary? [we’ll go over how to quote and paraphrase next class]

- Style: Has the writer maintained an objective tone throughout the summary? Is the summary carefully edited for clear communication?

Point out that this is a hierarchy. That is, the items at the top of the list are more important to a successful summary than are the items at the bottom of the list.

Transition let’s use these criteria to workshop the draft you brought in today.

Present the following prompts on an overhead transparency, and ask students to work through them with their own summaries (anyone without a summary can work on drafting one now). Explain how they reflect the criteria you just reviewed so that students don’t think of them simply as a checklist.

Summary Self Workshop

This workshop will help you determine how well you have accomplished the goals of representing the writer’s argument both accurately and objectively.1. Underline the sentence(s) in which you have restated the author’s thesis.

2. Circle the author’s name, the date of publication, and the title of the magazine or newspaper in which the article was published.

3. Put a star by each reason or key point.

4. Draw a box around each author tag.

5. Draw [brackets] around anything superfluous: any of your own opinions or reactions and/or minutiae from the article (evidence, anecdotes, etc.).Now, look over your paper. You should have: an underlined sentence or two, three circles, a few stars, and a few boxes. If any of those things are missing, make a note to yourself that you need to add them in revision. If you have anything in brackets, be sure to remove them in revision.

If you're concerned that you will run out of time, you might consider discussing criteria one at a time and asking students to look at their own summaries to see if they meet the criterion. For example, you could first explain "Accuracy," then ask students to underline the thesis and reasons and then make a marginal note about whether they are represented accurately. Then you would move on to "Objectivity." This way, if you don't have time to get through all the criteria today, you can address them Wednesday.

Collect the summaries, with however much of the self-workshop done. You can read through these to assess students' progress toward summary goals. You might make a single comment on each summary to let students know how they are doing on accuracy and/or objectivity. You can look at how the class as a whole is doing on other criteria and address their strengths and weaknesses in Wednesday's lesson. Collecting summaries today will also help hold students accountable for homework.

Today you can begin to assign homework in the way you will do so throughout the rest of the semester. If you plan to post homework to the Writing Studio, it is fine to remind students of that and simply talk through the homework assignment. You might continue to put the homework on the overhead and/or create handouts, but be aware that your students might come to rely on that and ignore the Writing Studio calendar. Some teachers choose to write the homework on the board with the agenda. Whatever you choose to do, today is the day to start the routine. Be sure to collect the inquiry list before students leave.

Homework for Wednesday

Access, print, and read [Instructors, add your choice of articles here: “Mass Natural” and/or “You Are What You Grow.” If you choose to assign both, be sure to specify which you want students to summarize, and be sure to adjust Wednesday’s lesson plan so that you have time to discuss the content of both].

Draft a summary of Pollan’s article. Bring a printed copy of your summary draft.

Find the Academic Summary assignment sheet under Assignments. Print it and bring it to class. (This is one option for dealing with assignment sheets. You may forgo this and simply make copies for the class and bring them on Wednesday.)

Wrap up today’s class by saying something like, next time, we’ll look at another article by Michael Pollan, and we’ll go over quoting and paraphrasing.

Connection to Next Class

Today you’ve emphasized the importance of taking time to understand what an author is saying. Next time, you won’t need to spend as much time on this because, presumably, students will read more closely this time around. Because you've focused on discussing the homework and you've collected it, any students who came unprepared today should be more inclined to prepare for Wednesday.

Day 5 (Wednesday, August 29)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

During today’s class students begin to see summary writing as a rhetorical act (that is, as a set of choices made to achieve a particular purpose with a particular audience).

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

Introducing the Academic Summary assignment helps prepare them to write it. Students will continue to build the close reading and summarizing skills they need to write academic summaries.

Prep

For today’s class you need to have reread the assigned readings. Since today’s class includes a number of potentially time-consuming activities, you might take a moment to assess the way you have been customizing the lesson plans for yourself, and make any changes that would help you stay organized, focused, etc. during class.

Materials

Inquiry list

Reading(s) for today with notes

Summary assignment sheets (if you plan to hand them out; if you assigned printing out the assignment sheet, ask those who forgot to look on with another student)

Overhead transparencies:

Directions for group activity

Reading quiz or WTL prompt

Quoting and paraphrasing

6-8 blank transparencies for group activity

Lead-in

For today’s class students have read another Pollan article, and they have drafted another summary. They may have questions about the summary assignment.

Activities

Take attendance in the same way you did on Monday.

Designate a student to add on to the inquiry list for today. Link to last class and preview your activities for today.

Design an activity that will review the content of and hold students accountable for the reading homework. Remember to put questions/prompts on an overhead transparency.

As you did on Monday, take time to check in with students about the summary writing and their understanding of the reading. Return the summaries you collected Monday and make some general comments to the class about the common strengths and weaknesses you found. You might also want to remind students of how homework fits into their overall grade and explain any marks or comments you made on their summaries.

If you assigned both “Mass Natural” and “You Are What You Grow,” you’ll need more time for this activity, probably:

Generate summary points with students by asking two or three students to come to the board with their summary and write out the thesis statement they identified. While students are doing this, talk with the rest of the group about how they identified the thesis, and what key points they chose to include.

Note: you could ask two or three students to write on the board before class begins (just be sure you don’t have a quiz question about Pollan’s thesis!).

Once you have a few theses on the board, compare them to each other. It’s likely that they will be somewhat similar, though if they vary greatly you’ll need to spend time determining why that is. It might be a matter of scope (maybe one student looked more narrowly at Pollan’s argument than another student, for example), it could be a genuine misreading (if so, try to lead the class to an understanding of that rather than evaluating it on the spot), or it could be something else. In any event, work with your students to come to a consensus about which of the thesis statements on the board is both objective and accurate. Point out (again) that there is not just one way of representing Pollan’s argument (though there are limits to what passes as accurate).

Ask students to share the key points they chose to include. You don’t need to list these on the board as you did last time; students should be getting this concept by now.

Transition we’re getting pretty good at reading to understand a writer’s argument, and that’s key to writing a successful academic summary. Let’s look now the Academic Summary assignment.

Ask students to take a few minutes to re-read the assignment sheet. Then, walk them through it (no need to read it word-for-word, but be sure to highlight the essentials) and allow students time to ask questions. If a student asks a question you don’t want to answer right away, simply say, “let me get back to you about that” and then be sure to return to it on Friday. Since you’ve already looked at the criteria, you don’t need to do that again. Show students the letter-grade descriptions and ask that they read them over before next class.

Transition For Friday, you will revise one of the summaries you've written and bring it to class for a peer response workshop. Some of you have probably done peer response workshops before. Let's talk about your experiences.

Ask students if they have done peer response in previous classes and what their experiences have been. Move toward generating a list of helpful and not-so-helpful types of feedback. You can collect these on a blank transparency so that you can bring them back on Friday when you introduce the peer response activity. Remind students of your goal for peer response--to get reader feedback on work-in-progress. This would be a good time to remind them of your workshop policy, emphasizing the need to come prepared with a draft.

Homework for Friday

Revise one of the summaries you've written. Bring a printed copy of your summary draft for a peer workshop on Friday.

Reread the summary assignment sheet and email with any questions you have.

Read pages 205-206 about paraphrasing and quoting, and jot down any questions that come up.

Wrap up today’s class by saying something like, next time, we’ll go over quoting and paraphrasing, and you’ll get a chance to get some feedback from a classmate.

Connection to Next Class

You’ve gotten students used to bringing their own writing into the classroom and so some of students’ nervousness about peer workshopping might be lessened. Next time, you’ll do a practice workshop before students trade papers to give each other feedback and that will give you a chance to address concerns and misconceptions about what workshops will be like in CO150.

Day 6 (Friday, August 31)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals

During today’s class, students will, on a small scale, engage in an academic community by participating in peer workshop.

Connection to Students’ Own Writing

The work students do with quoting and paraphrasing will help them write effective summaries. Student writing becomes the focus of today’s class during the peer workshop.

Prep

For today’s class you need to have recorded the quizzes or WTLs from last time and to have made a list of discussion questions in case you have extra time at the end of class.

Materials

Inquiry list

Reading(s) for today with notes

Workshop handouts

Overhead transparencies:

Paraphrasing and quoting

Peer response guidelines you generated on Wednesday

Lead-in

For today’s class students have drafted another summary. They may have questions about the summary assignment, and they may be apprehensive about the prospect of peer workshopping.

Activities

Take attendance in the same way you did on Monday.

Designate a student to add on to the inquiry list for today. Link to last class and preview your activities for today.

Introduce the concepts of quoting and paraphrasing first (use an overhead transparency to save yourself having to write everything out on the board):

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Both quoting and paraphrasing are methods of representing another writer’s language and ideas in your own writing. Since summary is a condensed version of another writer’s ideas, summary depends heavily on quoting and paraphrasing.

Quoting: inserting another writer’s exact words into your writing. The exact words are contained within quotation marks. For example:

Peter Singer says, “Going vegetarian is a good option, and going vegan, better still. But if you continue to eat animal products, at least boycott factory farms.”