Day 2 (Wednesday, August 27)

Lesson Objectives

Students will

Connection to Course Goals. Today’s class introduces the idea of academic inquiry that will be central to this course, as well as the close reading skills that will be important in the Academic Summary assignment.

Prep

Before today's class, be sure you have reread "Responses to the IPCC” and written your own lesson plan.

Materials

Your notes about the readings for the first unit

List of questions/prompts for class discussion

Prentice Hall Guide (“Responses to the IPCC” annotated for each author's thesis and reasons)

Overhead Transparencies:

Identifying Thesis Statements activity instructions

Homework (or make handouts for homework—do the same thing that you did on Monday)

Lead-In

For today's class, students have read "Responses to the IPCC,” have looked for thesis statements, and are expecting to discuss the reading. It's not uncommon to have a few students come to class the second day without having done the homework, or for new students to show up. Any unprepared student can join with a peer to look on with the reading and will be able to follow along during class. Arrange a way to help students with any problems (couldn’t log on to Writing Studio, bought the wrong textbook, etc.), but plan on a quiz or other means of holding students accountable for the reading assignments. Remind students of the upcoming limited add/drop policy deadlines. Refer them to the yellow sheet you handed out on the first day.

Activities

If you arrive to class a few minutes early, you might write the "agenda" on the board. A brief list of today's activities could go something like: "Introduce Inquiry/ Write-to-Learn/Quiz / Discuss and reading/ Identify thesis statements." If you choose to do this, make it a reliable routine.

Attendance (2-3 minutes)

Take care of any remaining registration issues (such as new students or students that were absent on the first day), and be sure to note which students are absent. You might take attendance by asking each student to describe one thing he or she remembers about a classmate from the getting-to-know-you activity last time.

Transition. Try something like: You'll be getting to know each other more in the next few weeks as we read and discuss issues related to climate change.

Introduce academic inquiry and question-at-issue (10 minutes)

Tip. Consistently emphasizing the link between sustained inquiry (here, into climate change) and college-level writing and thinking will help to defuse complaints from those students who will be “bored” with the subject.

Take some time to explain what you'll be asking students to read about, and why. Take a look back at the introduction to Phase 1 for some possible explanations. Here's a sample explanation:

Since writing is in essence a carefully-arranged record of thought, we need something thought-worthy to discuss as we practice writing strategies this semester. In the first few weeks of CO150, we'll inquire into questions about climate change. We'll read several magazine and newspaper articles written about climate and energy issues, each of which somehow addresses the question, "What should we do about climate change?" We're going to look at how these articles explore and answer this question, how they appeal to readers, how well they argue their points, and how they go about accomplishing these goals in writing. Later on in the semester, you'll pursue an inquiry of your own; after having looked so closely at the inquiries pursued by these writers, you'll be well prepared to make your own choices as you research and write.

Explain the inquiry list. Here’s a sample explanation:

As we work over the next few weeks, we will be keeping track of the questions and terms we want to know more about. I started a list as I re-read today’s reading. During each class session, someone will be in charge of adding questions raised by our reading and discussions to the list.

Read a few things from the list, and then assign a “list-keeper” for today. The "list-keeper" should listen especially carefully during discussions to make a record of the ideas and questions that come up. The list-keeper can also add questions of his/her own.

Transition. Since we'll be discussing this question quite a bit in the next few weeks, let's take some time to gather initial ideas now.

Assign a Write-to-Learn (WTL) (5-10 minutes)

Prepare an overhead transparency with instructions:

Write-to-Learn

On a sheet you can turn in, please write for a few minutes in response to the following questions:

Transition. Let’s see what you all wrote about.

Conduct a class discussion

Ask students to share some of their answers to the WTL questions. Have your own list of questions handy, too, so you can facilitate discussion as needed.

Collect the WTLs (1-2 minutes)

Some students may not be finished; tell them that they can turn in what they have and that you're not grading this (if you will be keeping track of WTLs and other small assignments, though, be sure students understand how you'll be doing this).

Transition. Let’s compare your ideas to those in the short articles we read for today.

Discuss "Responses to the IPCC" (10 minutes)

Get the students thinking about their responses to the WTL by asking questions such as "What did you find most interesting or surprising?" or "Which arguments are persuasive?" As students offer answers, encourage them to talk to each other by rephrasing their comments as you understood them and asking another student if he or she agrees, or asking "Who had a different reaction?" Don't hesitate to ask for clarification. If your students are very reluctant to speak, give them a WTL and then ask for some responses. If your students are overly-exuberant, keep track of time so that you can move forward with class after 10 minutes or so.

Tip. Calling on students by name will make them feel more engaged with the class, keep momentum up in the discussion, and give you more opportunity to memorize their names.

Transition. These reactions show that, often, writing gets a conversation going.

Introduce the idea of writing as conversation (3-5 minutes)

Explain the ways in which writing is similar to conversation. Here’s a sample explanation:

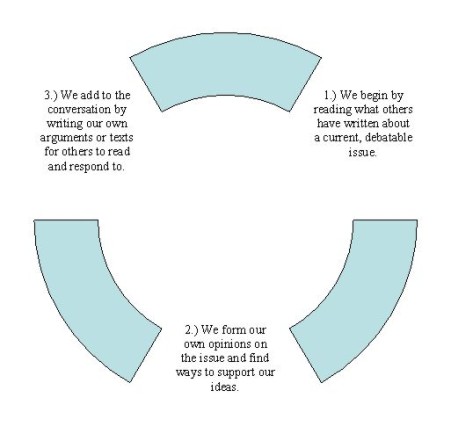

Like a conversation, writing involves exchanges of ideas that help us shape our own ideas and opinions. It would be foolish to open your mouth the moment you join a group of people engaged in conversation—instead, you listen for a few moments to understand what’s being discussed. Then, when you find that you have something to offer, you wait until an appropriate moment to contribute. We all know what happens to people who make off-topic, insensitive, inappropriate, or otherwise ill-considered remarks in a conversation.

The following is a visual representation of the way in which this course is designed around the writing as conversation metaphor. Before explaining, present it to students on an overhead, or draw it on the board:

Tip. This image can be enlarged to make a more visible overhead.

Once the students can see the image, explain:

Right now, we are at the first stage: reading what others have written. That is, we are listening in on the conversation. Later in the semester, we will conduct research to form our own opinions and add to the conversation.

Next, explain why you asked students to look for thesis statements. Here’s a sample explanation:

An important part of academic inquiry is being able to set aside ones’ own biases and preconceived ideas and really listen to what others are saying about the question-at-issue. This isn’t to say that readers don’t have reactions and responses but that it’s essential to be able to distinguish between subjective reactions to what the writer has said and an objective understanding of what the writer has said.

Transition. We rarely begin a conversation with a thesis statement announcing what we will say; likewise, writers don’t always begin with a thesis statement.

Group activity: identifying thesis statements (8-10 minutes)

Tip. You might point out that a thesis is often a response to a critical question, and ask students to think of questions the “Responses to the IPCC” writers are trying to answer.

Take time to define "thesis statement." There are many ways of defining this term; for our purposes a definition such as "the main idea that the writer wants to communicate to readers" works well. You might ask students what other words they’ve associated with “thesis,” such as “central claim,” “primary argument,” etc.

How can a reader find a thesis statement? Brainstorm ideas.

Now, give students a chance to practice this in small groups. Give instructions for group work on an overhead before you divide students into groups, and then assign them one of the IPCC responses from the PHG.

Identifying Thesis Statements

Work with your group to identify the thesis statement in one of the "Responses to the IPCC" essays.

If you disagree, try to figure out why, and try to reach a consensus.

In a few minutes, you'll report your findings back to the class.

Have students count off from 1 through 4 to create groups (all 1’s will group together, all 2’s together, and so on). Direct groups to specific areas of the room to work. Give groups a chance to say "hello" to each other, and then remind them of the task at hand.

It probably won't take groups a lot of time to do this; float among the groups to get a sense of their questions and keep them on task. Ask the first two groups finished to come to the front of the room and write the thesis statement they came up with on the board.

Once you have two theses on the board, talk them through with the class. Ask groups to explain why and how they identified this particular thesis, and ask the class if they agree with this group's identification. You can refer to your own notes to add on to (or to correct, if needed) what the groups have come up with. Remind students that thesis statements don't always come in the first paragraph, nor are they always neatly packaged in one obvious sentence.

Transition. Perhaps: Locating key points is an important part of academic inquiry. Try to key in on the most important points in the lecture by Scott Denning tonight so that we can discuss them on Friday.

Assign Homework for Friday (3-5 minutes)

Tip. The “File Folders” section of your Writing Studio class page is one method of making articles available to students, but students may also retrieve articles through Morgan Library databases. See appendix for a student-ready handout with directions for retrieving articles from library databases

Conclude class

Conclude class by saying something like, next week we will continue with our work of academic inquiry by working more on summary and by generating inquiry questions as we talk further about issues related to climate change.

Connection to Next Class

Take time to read over today's WTLs to assess students' prior knowledge of and opinions about the question-at-issue, to casually assess their writing abilities, and to add to the list of terms and questions for discussion and further inquiry.

On Friday, you will continue on with concepts you introduced today. You’ll move from identifying an author’s thesis to identifying the argument and summarizing it.