Note: The beginning of Portfolio 3 marks a new stage in your lesson planning. If you have not done so already, you should begin creating your own activities to accomplish the course goals. To support your efforts to accomplish this, we have provided more detailed discussion of teaching goals and have introduced a new section entitled “Resources.” If you have any questions about developing your lesson plans, please see Mike, Steve, Kate, Sarah, Kerri, Sue, Paul, or Liz.

Discuss what claims imply about development, reasoning, and evidence. Ask students to consider what types of evidence they’ll need based on the types of claims they might have. For example, a claim of value would necessitate a list of criteria, while a claim of solution would likely require evidence to prove both that a problem exists and that this solution would work or is better than other possibilities. Also, remind students that types of claims will suggest different types of proof. The PHG is set up to focus on different types of claims in different chapters. Ask students to review the chapter that deals with their type of claim.

Type of Claim:

Value - "Evaluating" Chapter

Solution/policy "Problem-solving" Chapter

Cause-effect "Cause-effect" Chapter

Fact "Informing" Chapter

- the criteria for intelligence (value)

- grades fail at representing these criteria (fact)

- portfolios will do a better job of meeting the criteria (fact)

Your discussion of a claim will depend on the audience and existing research. For example, if research has already shown that grades don't reflect intelligence, a writer could quickly support this sub claim and then focus on the solution -- using portfolios instead. However, if there is no evidence to support the claim that grades fail to represent intelligence, the focus for the argument should be on proving this claim.

The two main objectives for this week are to have students construct their claims and arguments and to have students think critically about how their target audience and context will influence the choices they make when writing their arguments. The techniques listed in the PHG will introduce students to classical forms of argumentation, but instructors should emphasize that audience and context are just as important as "forms" when making choices about content and organization. To write successfully, students will need to think about their readers' needs and interests and shape their arguments accordingly. The Context and Audience Analysis Report is designed to help students write for real world audiences. It serves the overall goals of encouraging students to be active participants in culture and enabling them to write for audiences beyond academia.

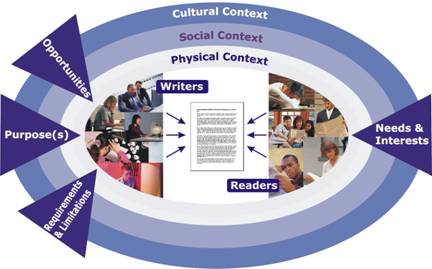

The Writing Situation Model:

Key points from the Writing Situation Model: Be sure to cover the following points (in whatever order feels right for you):

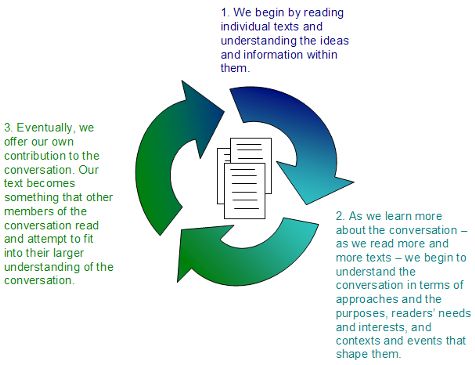

The “Great Circle of Writing” Model: This model helps students see the shift in their roles as writers that takes place as they join, learn about, and eventually contribute to a conversation about a publicly debated issue.

Points to bring up about the Great Circle of Writing Model:

· We begin as readers who encounter texts as a way to learn and explore what is happing culturally and socially. (Portfolio 1)

· Then, we become informed readers - drawn to certain specific issue that we want to learn more about. That is, we became accountable members of the conversation. (Portfolio 2)

· We read and research various texts to locate the "conversation" that surrounds the issue we're interested in (find out what groups or individuals, who are active in writing about the issue, are saying). (Portfolio 2)

· Then, we analyze these texts to figure out how they are shaped by cultural and social influences. And in turn, we consider how the texts that get produced are shaping society and culture. (Portfolio 2)

· Once we've critically examined the existing viewpoints on an issue, we become critical thinkers and informed writers. We then use our observations and critical thinking skills to construct new arguments. (Portfolio 3)

· We write our own arguments for public discourse (a specific group of readers in society) in the hope that our opinions and views will influence society and culture. (Portfolio 3)

· Through this process, we become active participants in society and culture. (Portfolio 3)

Sample Brainstorming Activity for Developing Claims and Arguments: The goal of this activity is to help students formulate possible arguments and claims for their issue. This activity takes place in front of the class using the white board. Lead students through one of the following strategies.

Strategy 1: Answer the question that you explored in Portfolio II to form an argument for Portfolio 3. For example:

If your research question for Portfolio II was:

> Who is responsible for intervening when child abuse is suspected?

Your argumentative claim for Portfolio III might be:

> The government needs to impose stricter laws to deter child abuse.

OR

> Teachers need to play a more active role in preventing child abuse.

Strategy 2: Brainstorm possible arguments by describing which parts of your issue you feel most strongly about. Then, imagine that you were involved in a conversation surrounding these aspects with some friends; what viewpoints might you offer? Which positions would you agree/disagree with? What overall arguments would you make?

Discuss Audience and Context for Arguments (15 - 20 minutes): Use this activity to model approaches to choosing a context and audience. Ask two or three students to put their claims up on the board (ask for volunteers - try pitching it as "free help" with their essay). Then, check to see if these claims are narrow and debatable. If they aren't, have students revise them to meet this criteria. If they are, use them as models for argumentation. Ask the class to brainstorm a list of possible audiences for each claim.

Use these points as a guide for this discussion:

- Look at the claim and ask - who needs to hear this argument?

- Who would be most interested in this argument?

- Who would be the most realistic audience to target (those who would actually read it and be affected by it)?

- Discuss how the argument would look differently based on each group of readers and their various needs and interests.

- Where might these different readers encounter this argument? Where would they be likely to read about it? (If students have difficulty generating specific contexts, tell them they'll need to do more research in this area to find out which contexts are available. One way to do learn about contexts is to look back at the journals they encountered when researching their issues in Portfolio II. Also, tell them to do some topic searches to find out where their issue is being talked about).

** Repeat the above process using 2 -3 sample claims.

The objective this week is to help students think about organizing and developing their arguments. By looking at sample arguments and discussing such things as claims, reasons, evidence, narration, and opposing arguments, students will begin to see that there are many approaches to writing arguments. We want to show students that there is no single correct way to organize or develop an argument. Rather, the effectiveness of an argument depends on the choices a writer makes in response to his/her audience and context. The HyperFolio assignment will allow students to practice making these choices with their own arguments.

Research and writing strategies and organization: Prepare a lecture, discussion or activity where you review the following strategies for developing and organizing different parts of an argument. If you prepare a lecture, we suggest that you ask students to take notes.

Writing Introductions

Review the types of strategies for creating introductions (also, see page 314 - 316 in the PHG for additional help with writing lead-ins and introductions):

· State the Topic: Come right out and say it. Tell your readers what your topic is, what the issue/conversation is you are focusing on, and what your argument aims to do.

· Define Your Argument: If your readers are familiar with disagreements among authors contributing to your conversation, you can get right to your main point—what you think should be done about the issue or what you think they should know about it. In other words, you can introduce your argument by leading with your thesis statement. By using your thesis statement in your introduction, you can let your readers know, for example, whether you are explaining something, making an argument to convince them of your points, offering a solution to a problem, etc…

· Define a Problem: Depending on how you define a problem, you’ll call attention to different solutions. There’s a tremendous difference, for instance, between saying, “We have a problem with education: our teachers are not prepared to teach the skills needed in the 21st century” and “We have a problem with education: our students can’t learn the skills needed in the 21st century.”

· Ask a Question: Asking a question invites your readers to become participants in the conversation you’ve joined by considering solutions to a problem or rethinking approaches to an issue or problem.

· Tell a Story: Everyone loves a story, assuming it’s told well and has a relevant point. Featured writer Patrick Crossland began his research project with a story about his brother Caleb, a senior in high school and a star wrestler who was beginning the process of applying to colleges and universities.

· Provide a Historical Account: Historical accounts can help your readers understand the origins of a particular situation, how the situation has changed over time, and how it has affected people.

· Lead with a Quotation: A quotation allows your readers to hear about the issue under discussion from someone who knows it well or has been affected by it. You can select a quotation that poses a question, defines a problem, or tells a story. You can also use quotations to provide a historical perspective.

· Review the Situation: You can provide a brief review of the situation, drawing on other sources or on your own synthesis of information about the issue. A brief review can be combined with other strategies, such as asking a question, defining a problem, or defining your argument.

Writing Conclusions

Introduce strategies for concluding an essay:

· Sum Up Your Argument: Offer a summary of the argument you’ve made in your document.

· Offer Additional Analysis: Extend your analysis of the issue by offering additional insights.

· Speculate about the Future: Reflect on what might happen next.

· Close with a Quotation: Select a quotation that does one of the following:

o sums up the points you’ve made in your document

o points to the future of the issue

o suggests a solution to a problem

o illustrates what you would like to see happen

· Close with a Story: Tell a story about the issue you’ve discussed in your document. The story might suggest a potential solution to the problem, offer hope about a desired outcome, or illustrate what might happen if a desired outcome doesn’t come to pass.

· Link to Your Introduction: This technique is sometimes called a “bookends” approach, since it positions your introduction and conclusion as related “ends” of your document. The basic idea is to turn you conclusion into an extension of your introduction:

o If your introduction used a quotation, end with a related quotation or respond to the quotation.

o If your introduction used a story, extend that story or retell it with a different ending.

o If your introduction asked a question, answer the question, restate the question, or ask a new question.

o If your introduction defined a problem, provide a solution to the problem, restate the problem, or suggest that readers need to move on to a new problem.

Using Illustrations

Find a few examples (from magazines or Web sites) to illustrate how some writers use illustrations to support their arguments. Pass these around in class:

Tell students that they will be expected to include some type of illustration (common to their chosen context) when shaping their final arguments.

Writing Narration

Consider where your argument fits into the larger, ongoing discussion about your issue. Then, provide some setting to show readers what you're responding to so that your essay isn't floating in space. The narration can be personal (a story that you've experienced) cultural (recent trends in society, or a speech or text that you're responding to) or political (recent government-supported actions). By connecting your issue to a something concrete, readers will realize its significance and see the reason for your argument.

Organizing Research

o chronological order

o cause > effect

o beneath multiple approaches or viewpoints

o compare and contrast

o strengths and weaknesses

o problems and solutions

Finding Substantial Evidence

You have already completed research to gain an understanding of the ongoing "conversation" about your particular issue, and to identify the range of positions on the issue. Now you'll need to do further research to 1.) consider the range of opposing arguments for your own argument and 2.) find substantial evidence to support your overall claim and sub claims. Use the following strategies to locate further research.

- Harper's - Independent

- Atlantic Monthly - The Economist

- New Republic - The Nation

- National Review - Business Week

- Utne Reader - The Christian Science Monitor

- The Humanist - Scientific American

(** Note that this list is by no means comprehensive.)

Using different Arguing Approaches (from PHG - more traditional vs. Rogerian)

This discussion should give students more of a sense of the different approaches or strategies available to them. Emphasize to students that their argument doesn’t have to be completely traditional or Rogerian. Instead, they might use Rogerian techniques for the most sensitive points in an argument that is otherwise more traditional.

Backwards Outline Analysis Directions: On a sheet of paper, (or on the board) write down the author’s main claim or the controlling idea in the essay. Divide the rest of the paper (or board) into three columns. Then complete the following tasks, one by one:

Note: As you design your lesson plans for this week, consider whether it would be best to meet in class, to schedule individual conferences, or to do both. If you believe conferences would be most valuable, cancel one or more of your class meetings this week and meet with students one on one. If you sense that students are having trouble with their research, spend a class in the library gathering sources. If you think students would benefit most from meeting formally, design a mini-workshop where students can peer review HyperFolio drafts in groups. Use this week to reinforce important concepts for Portfolio 3 and to catch up before Thanksgiving Break.

The activities this week support the concept that writing is a process involving collaboration and revision. By interacting with other writers (through research), peers, and instructors, students allow their previous ideas to take on new shapes. They make crucial decisions about content development based on observations made during research or the feedback received from potential readers.

Individual Conferences: Plan to spend 10 to 15 minutes per student. During the conferences, focus on these main concerns:

· Do they have a focused, debatable overall claim?

· Do they have a clear sense of why they’re writing on this issue in the first place?

· Do they have a clear sense of purpose in why they’re writing their argument for their defined audience? Does the claim fit the purpose?

· Are the audience, purpose and focus they’ve identified coherent?

· Do they understand what evidence they’ll need to support their sub-claims? What types of evidence do they plan to use? What evidence do they already have that can work?

Learning to write appeals and to avoid logical fallacies will help students construct effective arguments. It also serves the larger course goal of developing critical thinking skills. To use appeals successfully, writers must have a strong sense of who their readers are. To avoid fallacies in argumentation, writers must critically examine their claims to ensure that they are being thorough, thoughtful, and fair.

Where to Look for Appeals:

A Group Activity for Helping Students Analyze Appeals: Have students break into small groups (3-4) and give each group one or two sample appeals to look at. Put the following questions on an overhead for each group to address:

Allow each group 3 minutes to share their sample text and present some of their findings to the class. After all groups have finished presenting, emphasize that writers should use appeals to make effective arguments, but that they should also respect their readers and use the appeals fairly to represent their points (not to distort reality).

A Role Play Activity to Practice Using Appeals: Use this activity to get students thinking about how to appeal to an audience to meet a specific purpose. First, prepare five different tasks that require students to develop appeals. Print the tasks out and cut them into separate strips to distribute in class.

Sample Tasks:

Then, break students into small groups (4 - 5) and have each group choose one strip at random. Once students have their strips, explain the following:

"Your group task is written on this slip of paper. Your group will have 10 minutes to develop an argument to persuade the rest of the class to act on. Someone from your group will then read your task to the class (the class will role play the designated audience) and you will have 5 - 7 minutes to present your argument as a group. Afterwards, the class will decide if your use of appeals was strong enough to persuade us to act on your argument. Be sure to anticipate opposing arguments along the way (as some of your peers may raise questions and objections to your claims). While developing appeals, also consider what your audience will value most. What are their needs and interests and how can you respond to these?"

Give students 10 minutes to prepare arguments before presenting. Tell students that they are free to add some inventive material to their situation (e.g. your cousin just got out of jail and he's feeling very low about himself - he needs a girlfriend to make him feel better). After each group presents, ask the class which parts of the argument were most effective, and which of the appeals worked best. Tell students to keep these observations in mind when writing appeals for their own arguments.

The activities for this week emphasize (1) the importance of ongoing revision during the writing process, (2) the role of document design and formatting in the preparation of polished essays, and (3) the use of illustrations (charts, graphs, images, animations, video, etc.) as persuasive and informative devices. In terms of revising, your overall goal is to help students understand that writing continues even after they've completed their first draft. It would be ideal if they begin to see and value the improvements made during this process of rewriting. In terms of document design and formatting, your goal is to help students understand, first, that they must adapt their documents for publication in a specific venue and, second, that (among other things) document design calls a reader’s attention to specific information and ideas. In terms of illustrations, your goal is to expand students’ understanding of “evidence.” Students should understand that, in addition to such devices as paraphrases and quotations, they can draw on a wide range of illustrations, tables, charts, and so on to support their arguments.

Backwards Outline Activity: The backwards outline activity encourages students to look closely at the organization, focus, and coherence of their essay by considering how each paragraph functions in relation to the overall claim. Students can complete a backwards outline on their own draft or on their peers’ drafts. Since the directions for this activity can seem complicated, you might try to lead students through each step verbally (announcing each task and waiting five-to-ten minutes for students to complete the step). The outline below is a guide. Revise it as you see fit.

Backwards Outline Workshop

Read through your draft once without making any marks. Then re-read it while completing the following steps:

1. On a separate sheet of paper, write down the main claim of the essay. Quote directly from the essay and/or put it in your own words.

2. Then, divide the sheet into three columns.

3. In the left hand column, number and summarize what each paragraph says. If there is more than one idea in the paragraph, list the ideas as separate points.

4. Review the list in the left-hand column and see if similar things show up in different parts of the draft. (e.g. Are both #2 and #8 examples that prove the same point? Do #4 and #7 bring up the same example?) If so, suggest some possible reorganizations on the reverse side of your outline (and/or on another sheet of paper).

5. In the middle-column, write a sentence that summarizes the connection you see between what each paragraph does and the overall claim at the top of the page. If you can’t see a connection, put a question mark in the column.

6. Look back to see if each connection is made obvious in the draft itself. Under each connection you’ve written, make a note of “obvious” or “not obvious”.

7. In the third column, write down connection you see between each paragraph (e.g. between paragraph one and paragraph two, between paragraph two and paragraph three, and so on). If you can’t see a connection, put a question mark in the column.

8. For those paragraphs where you could see a connection, go back and examine the draft to see if the author has provided a transition for the reader explaining this connection. Mark each connection you listed with a note of “transition” or “no transition.”

9. Based on your analysis of the organization and coherence of this essay, make suggestions about how to re-organize and where stronger connections are needed. In your suggestions, be sure to consider whether any lack of clarity in organization, coherence, or evidence may result from the claim itself (i.e. ask whether the organization is hard to follow because the claim is trying to prove too much).

10. Finally, re-examine the draft one more time for evidence and provide suggestions about where more examples or proof are needed to support the argument.

11. When you receive comments on your draft, use them during revision.